Who Invented Homework and Why

Who Created Homework?

Italian pedagog, Roberto Nevilis, was believed to have invented homework back in 1905 to help his students foster productive studying habits outside of school. However, we'll sound find out that the concept of homework has been around for much longer.

Homework, which most likely didn't have a specific term back then, already existed even in ancient civilizations. Think Greece, Rome, and even ancient Egypt. Over time, homework became standardized in our educational systems. This happened naturally over time, as the development of the formal education system continued.

In this article, we're going to attempt to find out who invented homework, and when was homework invented, and we're going to uncover if the creator of homework is a single person or a group of them. Read this article through to the end to find out.

Who Invented Homework and When?

It is commonly believed that Roberto Nevelis from Venice, Italy, is the originator of homework. Depending on various sources, this invention is dated either in the year 1095 or 1905.

It might be impossible to answer when was homework invented. A simpler question to ask is ‘what exactly is homework?’.

If you define it as work assigned to do outside of a formal educational setup, then homework might be as old as humanity itself. When most of what people studied were crafts and skills, practicing them outside of dedicated learning times may as well have been considered homework.

Let’s look at a few people who have been credited with formalizing homework over the past few thousand years.

Roberto Nevilis

Stories and speculations on the internet claim Roberto Nevilis is the one who invented school homework, or at least was the first person to assign homework back in 1905.

Who was he? He was an Italian educator who lived in Venice. He wanted to discipline and motivate his class of lackluster students. Unfortunately, claims online lack factual basis and strong proof that Roberto did invent homework.

Homework, as a concept, predates Roberto, and can't truly be assigned to a sole inventor. Moreover, it's hard to quantify where an idea truly emerges, because many ideas emerge from different parts of the world simultaneously or at similar times, therefore it's hard to truly pinpoint who invented this idea.

Pliny the Younger

Another culprit according to the internet lived a thousand years before Roberto Nevilis. Pliny the Younger was an oratory teacher in the first century AD in the Roman Empire.

He apparently asked his students to practice their oratory skills at home, which some people consider one of the first official versions of homework.

It is difficult to say with any certainty if this is the first time homework was assigned though because the idea of asking students to practice something outside classes probably existed in every human civilization for millennia.

Horace Mann

To answer the question of who invented homework and why, at least in the modern sense, we have to talk about Horace Mann. Horace Mann was an American educator and politician in the 19th century who was heavily influenced by movements in the newly-formed German state.

He is credited for bringing massive educational reform to America, and can definitely be considered the father of modern homework in the United States. However, his ideas were heavily influenced by the founding father of German nationalism Johann Gottlieb Fichte.

After the defeat of Napoleon and the liberation of Prussia in 1814, citizens went back to their own lives, there was no sense of national pride or German identity. Johann Gottlieb Fichte came up with the idea of Volkschule, a mandatory 9-year educational system provided by the government to combat this.

Homework already existed in Germany at this point in time but it became a requirement in Volkschule. Fichte wasn't motivated purely by educational reform, he wanted to demonstrate the positive impact and power of a centralized government, and assigning homework was a way of showing the state's power to influence personal and public life.

This effort to make citizens more patriotic worked and the system of education and homework slowly spread through Europe.

Horace Mann saw the system at work during a trip to Prussia in the 1840s and brought many of the concepts to America, including homework.

Who Invented Homework and Why?

Homework's history and objectives have evolved significantly over time, reflecting changing educational goals. Now, that we've gone through its history a bit, let's try to understand the "why". The people or people who made homework understood the advantages of it. Let's consider the following:

- Repetition, a key factor in long-term memory retention, is a primary goal of homework. It helps students solidify class-learned information. This is especially true in complex subjects like physics, where physics homework help can prove invaluable to learning effectively.

- Homework bridges classroom learning with real-world applications, enhancing memory and understanding.

- It identifies individual student weaknesses, allowing focused efforts to address them.

- Working independently at their own pace, students can overcome the distractions and constraints of a classroom setting through homework.

- By creating a continuous learning flow, homework shifts the perspective from viewing each school day as isolated to seeing education as an ongoing process.

- Homework is crucial for subjects like mathematics and sciences, where repetition is necessary to internalize complex processes.

- It's a tool for teachers to maximize classroom time, focusing on expanding understanding rather than just drilling fundamentals.

- Responsibility is a key lesson from homework. Students learn to manage time and prioritize tasks to meet deadlines.

- Research skills get honed through homework as students gather information from various sources.

- Students' creative potential is unleashed in homework, free from classroom constraints.

The person or people who made school and homework understood the plethora of advantages homework had and the positive effect it had on students' cognitive functions over time.

Struggling with your Homework?

Get your assignments done by real pros. Save your precious time and boost your marks with ease.

Who Invented Homework: Development in the 1900s

Thanks to Horace Mann, homework had become widespread in the American schooling system by 1900, but it wasn't universally popular amongst either students or parents.

The early 1900s homework bans

In 1901, California became the first state to ban homework. Since homework had made its way into the American educational system there had always been people who were against it for some surprising reasons.

Back then, children were expected to help on farms and family businesses, so homework was unpopular amongst parents who expected their children to help out at home. Many students also dropped out of school early because they found homework tedious and difficult.

Publications like Ladies' Home Journal and The New York Times printed statements and articles about the detrimental effects of homework on children's health.

The 1930 child labor laws

Homework became more common in the U.S. around the early 1900s. As to who made homework mandatory, the question remains open, but its emergence in the mainstream sure proved beneficial. Why is this?

Well, in 1930, child labor laws were created. It aimed to protect children from being exploited for labor and it made sure to enable children to have access to education and schooling. The timing was just right.

Speaking of homework, if you’re reading this article and have homework you need to attend to, send a “ do my homework ” request on Studyfy and instantly get the help of a professional right now.

Progressive reforms of the 1940s and 50s

With more research into education, psychology and memory, the importance of education became clear. Homework was understood as an important part of education and it evolved to become more useful and interesting to students.

Homework during the Cold War

Competition with the Soviet Union fueled many aspects of American life and politics. In a post-nuclear world, the importance of Science and Technology was evident.

The government believed that students had to be well-educated to compete with Soviet education systems. This is the time when homework became formalized, accepted, and a fundamental part of the American educational system.

1980s Nation at Risk

In 1983 the National Commission on Excellence in Education published Nation at Risk:

The Imperative for Educational Reform, a report about the poor condition of education in America. Still in the Cold War, this motivated the government in 1986 to talk about the benefits of homework in a pamphlet called “What Works” which highlighted the importance of homework.

Did you like our Homework Post?

For more help, tap into our pool of professional writers and get expert essay editing services!

Who Invented Homework: The Modern Homework Debate

Like it or not, homework has stuck through the times, remaining a central aspect in education since the end of the Cold War in 1991. So, who invented homework 😡 and when was homework invented?

We’ve tried to pinpoint different sources, and we’ve understood that many historical figures have contributed to its conception.

Horace Mann, in particular, was the man who apparently introduced homework in the U.S. But let’s reframe our perspective a bit. Instead of focusing on who invented homework, let’s ask ourselves why homework is beneficial in the first place. Let’s consider the pros and cons:

- Homework potentially enhances memory.

- Homework helps cultivate time management, self-learning, discipline, and cognitive skills.

- An excessive amount of work can cause mental health issues and burnout.

- Rigid homework tasks can take away time for productive and leisurely activities like arts and sports.

Meaningful homework tasks can challenge us and enrich our knowledge on certain topics, but too much homework can actually be detrimental. This is where Studyfy can be invaluable. Studyfy offers homework help.

All you need to do is click the “ do my assignment ” button and send us a request. Need instant professional help? You know where to go now.

Frequently asked questions

Who made homework.

As stated throughout the article, there was no sole "inventor of homework." We've established that homework has already existed in ancient civilizations, where people were assigned educational tasks to be done at home.

Let's look at ancient Greece; for example, students at the Academy of Athens were expected to recite and remember epic poems outside of their institutions. Similar practices were going on in ancient Egypt, China and Rome.

This is why we can't ascertain the sole inventor of homework. While history can give us hints that homework was practiced in different civilizations, it's not far-fetched to believe that there have been many undocumented events all across the globe that happened simultaneously where homework emerged.

Why was homework invented?

We've answered the question of "who invented homework 😡" and we've recognized that we cannot pinpoint it to one sole inventor. So, let's get back to the question of why homework was invented.

Homework arose from educational institutions, remained, and probably was invented because teachers and educators wanted to help students reinforce what they learned during class. They also believed that homework could improve memory and cognitive skills over time, as well as instill a sense of discipline.

In other words, homework's origins can be linked to academic performance and regular students practice. Academic life has replaced the anti-homework sentiment as homework bans proved to cause partial learning and a struggle to achieve conceptual clarity.

Speaking of, don't forget that Studyfy can help you with your homework, whether it's Python homework help or another topic. Don't wait too long to take advantage of expert help when you can do it now.

Is homework important for my learning journey?

Now that we've answered questions on who made school and homework and why it was invented, we can ask ourselves if homework is crucial in our learning journey.

At the end of the day, homework can be a crucial step to becoming more knowledgeable and disciplined over time.

Exercising our memory skills, learning independently without a teacher obliging us, and processing new information are all beneficial to our growth and evolution. However, whether a homework task is enriching or simply a filler depends on the quality of education you're getting.

The Big Question: Who Invented Homework?

Crystal Bourque

Love it or hate it, homework is part of student life.

But what’s the purpose of completing these tasks and assignments? And who would create an education system that makes students complete work outside the classroom?

This post contains everything you’ve ever wanted to know about homework. So keep reading! You’ll discover the answer to the big question: who invented homework?

The Inventor of Homework

The myth of roberto nevilis: who is he, the origins of homework, a history of homework in the united states, 5 facts about homework, types of homework.

- What’s the Purpose of Homework?

- Homework Pros

- Homework Cons

When, How, and Why was Homework Invented?

Daniel Jedzura/Shutterstock.com

To ensure we cover the basics (and more), let’s explore when, how, and why was homework invented.

As a bonus, we’ll also cover who invented homework. So get ready because the answer might surprise you!

It’s challenging to pinpoint the exact person responsible for the invention of homework.

For example, Medieval Monks would work on memorization and practice singing. Ancient philosophers would read and develop their teachings outside the classroom. While this might not sound like homework in the traditional form we know today, one could argue that these methods helped to form the basic structure and format.

So let’s turn to recorded history to try and identify who invented homework and when homework was invented.

Pliny the Younger

Credit: laphamsquarterly.org

We can trace the term ‘homework’ back to ancient Rome. Pliny the Younger (61—112 CE), an oratory teacher, often told his students to practice their public speaking outside class.

Pliny believed that the repetition and practice of speech would help students gain confidence in their speaking abilities.

Johann Gottlieb Fichte

Credit: inlibris.com

Before the idea of homework came to the United States, Germany’s newly formed nation-state had been giving students homework for years.

It wasn’t until German Philosopher Johann Gottlieb Fichte (1762—1814) helped to develop the Volksschulen (People’s Schools) that homework became mandatory.

Fichte believed that the state needed to hold power over individuals to create a unified Germany. A way to assert control over people meant that students attending the Volksshulen were required to complete assignments at home on their own time.

As a result, some people credit Fichte for being the inventor of homework.

Horace Mann

Credit: commons.wikimedia.org

The idea of homework spread across Europe throughout the 19th century.

So who created homework in the United States?

Horace Mann (1796—1859), an American educational reformer, spent some time in Prussia. There, he learned more about Germany’s Volksshulen and homework practices.

Mann liked what he saw and brought this system back to America. As a result, homework rapidly became a common factor in students’ lives across the country.

Credit: medium.com

If you’ve ever felt curious about who invented homework, a quick online search might direct you to a man named Roberto Nevilis, a teacher in Venice, Italy.

As the story goes, Nevilis invented homework in 1905 (or 1095) to punish students who didn’t demonstrate a good understanding of the lessons taught during class.

This teaching technique supposedly spread to the rest of Europe before reaching North America.

Unfortunately, there’s little truth to this story. If you dig a little deeper, you’ll find that these online sources lack credible sources to back up this myth as fact.

In 1905, the Roman Empire turned its attention to the First Crusade. No one had time to spare on formalizing education, and classrooms didn’t even exist. So how could Nevilis spread the idea of homework when education remained so informal?

And when you jump to 1901, you’ll discover that the government of California passed a law banning homework for children under fifteen. Nevilis couldn’t have invented homework in 1905 if this law had already reached the United States in 1901.

Inside Creative House/Shutterstock.com

When it comes to the origins of homework, looking at the past shows us that there isn’t one person who created homework. Instead, examining the facts shows us that several people helped to bring the idea of homework into Europe and then the United States.

In addition, the idea of homework extends beyond what historians have discovered. After all, the concept of learning the necessary skills human beings need to survive has existed since the dawn of man.

More than 100 years have come and gone since Horace Mann introduced homework to the school system in the United States.

Therefore, it’s not strange to think that the concept of homework has changed, along with our people and culture.

In short, homework hasn’t always been considered acceptable. Let’s dive into the history or background of homework to learn why.

Homework is Banned! (The 1900s)

Important publications of the time, including the Ladies’ Home Journal and The New York Times, published articles on the negative impacts homework had on American children’s health and well-being.

As a result, California banned homework for children under fifteen in 1901. This law, however, changed again about a decade later (1917).

Children Needed at Home (The 1930s)

Formed in 1923, The American Child Health Association (ACHA) aimed to decrease the infant mortality rate and better support the health and development of the American child.

By the 1930s, ACHA deemed homework a form of child labor. Since the government recently passed laws against child labor , it became difficult to justify homework assignments.

Studio Romantic/Shutterstock.com

A Shift in Ideas (The 1940s—1950s)

During the early to mid-1900s, the United States entered the Progressive Era. As a result, the country reformed its education system to help improve students’ learning.

Homework became a part of everyday life again. However, this time, the reformed curriculum required teachers to make the assignments more personal.

As a result, students would write essays on summer vacations and winter breaks, participate in ‘show and tell,’ and more.

These types of assignments still exist today!

Homework Today (The 2000s)

In 2022, the controversial nature of homework is once again a hot topic of discussion in many classrooms.

According to one study , more than 60% of college and high school students deal with mental health issues like depression and anxiety due to homework. In addition, the large number of assignments given to students takes away the time students spend on other interests and hobbies. Homework also negatively impacts sleep.

As a result, some schools have implemented a ban or limit on the amount of homework assigned to students.

Test your knowledge and check out these other facts about homework:

- Horace Mann is also known as the ‘father’ of the modern school system (read more about it here ).

- With a bit of practice, homework can improve oratory and writing skills. Both are important in a student’s life at all stages.

- Homework can replace studying. Completing regular assignments reduces the time needed to prepare for tests.

- Homework is here to stay. It doesn’t look like teachers will stop assigning homework any time soon. However, the type and quantity of homework given seems to be shifting to accommodate the modern student’s needs.

- The optimal length of time students should spend on homework is one to two hours. Students who spent one to two hours on homework per day scored higher test results.

Ground Picture/Shutterstock.com

The U.S. Department of Education provides teachers with plenty of information and resources to help students with homework.

In general, teachers give students homework that requires them to employ four strategies. The four types of homework types include:

- Practice: To help students master a specific skill, teachers will assign homework that requires them to repeat the particular skill. For example, students must solve a series of math problems.

- Preparation: This type of homework introduces students to the material they will learn in the future. An example of preparatory homework is assigning students a chapter to read before discussing the contents in class the next day.

- Extension: When a teacher wants to get students to apply what they’ve learned but create a challenge, this type of homework is assigned. It helps to boost problem-solving skills. For example, using a textbook to find the answer to a question gets students to problem-solve differently.

- Integration: To solidify the learning experience for students, teachers will create a task that requires the use of many different skills. An example of integration is a book report. Completing integration homework assignments help students learn how to be organized, plan, strategize, and solve problems on their own.

Ultimately, the type of homework students receive should have a purpose, be focused and clear, and challenge students to problem solve while integrating lessons learned.

What’s the Purpose of Homework?

LightField Studios/Shutterstock.com

Homework aims to ensure students understand the information they learn in class. It also helps teachers to assess a student’s progress and identify strengths and weaknesses.

For example, teachers use different types of homework like book reports, essays, math problems, and more to help students demonstrate their understanding of the lessons learned.

Does Homework Improve the Quality of Education?

Homework is a controversial topic today. Educators, parents, and even students often question whether homework is beneficial in improving the quality of education.

Let’s explore the pros and cons of homework to try and determine whether homework improves the quality of education in schools.

Homework Pros:

- Time Management Skills : Assigning homework with a due date helps students to develop a schedule to ensure they complete tasks on time.

- More Time to Learn : Students encounter plenty of distractions at school. It’s also challenging for students to grasp the material in an hour or less. Assigning homework provides the student the opportunity to understand the material.

- Improves Research Skills : Some homework assignments require students to seek out information. Through homework, students learn where to seek out good, reliable sources.

Homework Cons:

- Reduced Physical Activity : Homework requires students to sit at a desk for long periods. Lack of movement decreases the amount of physical activity, often because teachers assign students so much homework that they don’t have time for anything else.

- Stuck on an Assignment: A student often gets stuck on an assignment. Whether they can’t find information or the correct solution, students often don’t have help from parents and require further support from a teacher.

- Increases Stress : One of the results of getting stuck on an assignment is that it increases stress and anxiety. Too much homework hurts a child’s mental health, preventing them from learning and understanding the material.

Some research shows that homework doesn’t provide educational benefits or improve performance.

However, research also shows that homework benefits students—provided teachers don’t give them too much. Here’s a video from Duke Today that highlights a study on the very topic.

Homework Today

Maybe one day, students won’t need to submit assignments or complete tasks at home. But until then, many students understand the benefits of completing homework as it helps them further their education and achieves future career goals.

Before you go, here’s one more question: how do you feel about homework? Do you think teachers assign too little or too much? Get involved and start a discussion in the comments!

The picture on the front page: Evgeny Atamanenko/Shutterstock.com

Today, sex education has become a crucial factor to ensuring the safety of our children….

The school year is now starting again and with that, the Internet is blowing up…

We encourage children not to complain and to cope with all hardships themselves. Yet at…

Subscribe now!

Glad you've joined us🎉🎉.

History Cooperative

The Homework Dilemma: Who Invented Homework?

The inventor of homework may be unknown, but its evolution reflects contributions from educators, philosophers, and students. Homework reinforces learning, fosters discipline, and prepares students for the future, spanning from ancient civilizations to modern education. Ongoing debates probe its balance, efficacy, equity, and accessibility, prompting innovative alternatives like project-based and personalized learning. As education evolves, the enigma of homework endures.

Table of Contents

Who Invented Homework?

While historical records don’t provide a definitive answer regarding the inventor of homework in the modern sense, two prominent figures, Roberto Nevelis of Venice and Horace Mann, are often linked to the concept’s early development.

Roberto Nevelis of Venice: A Mythical Innovator?

Roberto Nevelis, a Venetian educator from the 16th century, is frequently credited with the invention of homework. The story goes that Nevelis assigned tasks to his students outside regular classroom hours to reinforce their learning—a practice that aligns with the essence of homework. However, the historical evidence supporting Nevelis as the inventor of homework is rather elusive, leaving room for skepticism.

While Nevelis’s role remains somewhat mythical, his association with homework highlights the early recognition of the concept’s educational value.

Horace Mann: Shaping the American Educational Landscape

Horace Mann, often regarded as the “Father of American Education,” made significant contributions to the American public school system in the 19th century. Though he may not have single-handedly invented homework, his educational reforms played a crucial role in its widespread adoption.

Mann’s vision for education emphasized discipline and rigor, which included assigning tasks to be completed outside of the classroom. While he did not create homework in the traditional sense, his influence on the American education system paved the way for its integration.

The invention of homework was driven by several educational objectives. It aimed to reinforce classroom learning, ensuring knowledge retention and skill development. Homework also served as a means to promote self-discipline and responsibility among students, fostering valuable study habits and time management skills.

Why Was Homework Invented?

The invention of homework was not a random educational practice but rather a deliberate strategy with several essential objectives in mind.

Reinforcing Classroom Learning

Foremost among these objectives was the need to reinforce classroom learning. When students leave the classroom, the goal is for them to retain and apply the knowledge they have acquired during their lessons. Homework emerged as a powerful tool for achieving this goal. It provided students with a structured platform to revisit the day’s lessons, practice what they had learned, and solidify their understanding.

Homework assignments often mirrored classroom activities, allowing students to extend their learning beyond the confines of school hours. Through the repetition of exercises and tasks related to the curriculum, students could deepen their comprehension and mastery of various subjects.

Fostering Self-Discipline and Responsibility

Another significant objective behind the creation of homework was the promotion of self-discipline and responsibility among students. Education has always been about more than just the acquisition of knowledge; it also involves the development of life skills and habits that prepare individuals for future challenges.

By assigning tasks to be completed independently at home, educators aimed to instill valuable study habits and time management skills. Students were expected to take ownership of their learning, manage their time effectively, and meet deadlines—a set of skills that have enduring relevance in contemporary education and beyond.

Homework encouraged students to become proactive in their educational journey. It taught them the importance of accountability and the satisfaction of completing tasks on their own. These life skills would prove invaluable in their future endeavors, both academically and in the broader context of their lives.

When Was Homework Invented?

The roots of homework stretch deep into the annals of history, tracing its origins to ancient civilizations and early educational practices. While it has undergone significant evolution over the centuries, the concept of extending learning beyond the classroom has always been an integral part of education.

Earliest Origins of Homework and Early Educational Practices

The idea of homework, in its most rudimentary form, can be traced back to the earliest human civilizations. In ancient Egypt , for instance, students were tasked with hieroglyphic writing exercises. These exercises served as a precursor to modern homework, as they required students to practice and reinforce their understanding of written language—an essential skill for communication and record-keeping in that era.

In ancient Greece , luminaries like Plato and Aristotle advocated for the use of written exercises as a tool for intellectual development. They recognized the value of practice in enhancing one’s knowledge and skills, laying the foundation for a more systematic approach to homework.

The ancient Romans also played a pivotal role in the early development of homework. Young Roman students were expected to complete assignments at home, with a particular focus on subjects like mathematics and literature. These assignments were designed to consolidate their classroom learning, emphasizing the importance of practice in mastering various disciplines.

READ MORE: Who Invented Math? The History of Mathematics

The practice of assigning work to be done outside of regular school hours continued to evolve through various historical periods. As societies advanced, so did the complexity and diversity of homework tasks, reflecting the changing needs and priorities of education.

The Influence of Educational Philosophers

While the roots of homework extend to ancient times, the ideas of renowned educational philosophers in later centuries further contributed to its development. John Locke, an influential thinker of the Enlightenment era, believed in a gradual and cumulative approach to learning. He emphasized the importance of students revisiting topics through repetition and practice, a concept that aligns with the principles of homework.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, another prominent philosopher, stressed the significance of self-directed learning. Rousseau’s ideas encouraged the development of independent study habits and a personalized approach to education—a philosophy that resonates with modern concepts of homework.

Homework in the American Public School System

The American public school system has played a pivotal role in the widespread adoption and popularization of homework. To understand the significance of homework in modern education, it’s essential to delve into its history and evolution within the United States.

History and Evolution of Homework in the United States

The late 19th century marked a significant turning point for homework in the United States. During this period, influenced by educational reforms and the growing need for standardized curricula, homework assignments began to gain prominence in American schools.

Educational reformers and policymakers recognized the value of homework as a tool for reinforcing classroom learning. They believed that assigning tasks for students to complete outside of regular school hours would help ensure that knowledge was retained and skills were honed. This approach aligned with the broader trends in education at the time, which aimed to provide a more structured and systematic approach to learning.

As the American public school system continued to evolve, homework assignments became a common practice in classrooms across the nation. The standardization of curricula and the formalization of education contributed to the integration of homework into the learning process. This marked a significant departure from earlier educational practices, reflecting a shift toward more structured and comprehensive learning experiences.

The incorporation of homework into the American education system not only reinforced classroom learning but also fostered self-discipline and responsibility among students. It encouraged them to take ownership of their educational journey and develop valuable study habits and time management skills—a legacy that continues to influence modern pedagogy.

Controversies Around Homework

Despite its longstanding presence in education, homework has not been immune to controversy and debate. While many view it as a valuable educational tool, others question its effectiveness and impact on students’ well-being.

The Homework Debate

One of the central controversies revolves around the amount of homework assigned to students. Critics argue that excessive homework loads can lead to stress, sleep deprivation, and a lack of free time for students. The debate often centers on striking the right balance between homework and other aspects of a student’s life, including extracurricular activities, family time, and rest.

Homework’s Efficacy

Another contentious issue pertains to the efficacy of homework in enhancing learning outcomes. Some studies suggest that moderate amounts of homework can reinforce classroom learning and improve academic performance. However, others question whether all homework assignments contribute equally to learning or whether some may be more beneficial than others. The effectiveness of homework can vary depending on factors such as the student’s grade level, the subject matter, and the quality of the assignment.

Equity and Accessibility

Homework can also raise concerns related to equity and accessibility. Students from disadvantaged backgrounds may have limited access to resources and support at home, potentially putting them at a disadvantage when it comes to completing homework assignments. This disparity has prompted discussions about the role of homework in perpetuating educational inequalities and how schools can address these disparities.

Alternative Approaches to Learning

In response to the controversies surrounding homework, educators and researchers have explored alternative approaches to learning. These approaches aim to strike a balance between reinforcing classroom learning and promoting holistic student well-being. Some alternatives include:

Project-Based Learning

Project-based learning emphasizes hands-on, collaborative projects that allow students to apply their knowledge to real-world problems. This approach shifts the focus from traditional homework assignments to engaging, practical learning experiences.

Flipped Classrooms

Flipped classrooms reverse the traditional teaching model. Students learn new material at home through video lectures or readings and then use class time for interactive discussions and activities. This approach reduces the need for traditional homework while promoting active learning.

Personalized Learning

Personalized learning tailors instruction to individual students’ needs, allowing them to progress at their own pace. This approach minimizes the need for one-size-fits-all homework assignments and instead focuses on targeted learning experiences.

The Ongoing Conversation

The controversies surrounding homework highlight the need for an ongoing conversation about its role in education. Striking the right balance between reinforcing learning and addressing students’ well-being remains a complex challenge. As educators, parents, and researchers continue to explore innovative approaches to learning, the role of homework in the modern educational landscape continues to evolve. Ultimately, the goal is to provide students with the most effective and equitable learning experiences possible.

Unpacking the Homework Enigma

Homework, without a single inventor, has evolved through educators, philosophers, and students. It reinforces learning, fosters discipline and prepares students. From ancient times to modern education, it upholds timeless values. Yet, controversies arise—debates on balance, efficacy, equity, and accessibility persist. Innovative alternatives like project-based and personalized learning emerge. Homework’s role evolves with education.

How to Cite this Article

There are three different ways you can cite this article.

1. To cite this article in an academic-style article or paper , use:

<a href=" https://historycooperative.org/who-invented-homework/ ">The Homework Dilemma: Who Invented Homework?</a>

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/71970990/05_nohomework_Jiayue_Li.0.jpg)

Filed under:

- The Highlight

Nobody knows what the point of homework is

The homework wars are back.

Share this story

- Share this on Facebook

- Share this on Twitter

- Share this on Reddit

- Share All sharing options

Share All sharing options for: Nobody knows what the point of homework is

As the Covid-19 pandemic began and students logged into their remote classrooms, all work, in effect, became homework. But whether or not students could complete it at home varied. For some, schoolwork became public-library work or McDonald’s-parking-lot work.

Luis Torres, the principal of PS 55, a predominantly low-income community elementary school in the south Bronx, told me that his school secured Chromebooks for students early in the pandemic only to learn that some lived in shelters that blocked wifi for security reasons. Others, who lived in housing projects with poor internet reception, did their schoolwork in laundromats.

According to a 2021 Pew survey , 25 percent of lower-income parents said their children, at some point, were unable to complete their schoolwork because they couldn’t access a computer at home; that number for upper-income parents was 2 percent.

The issues with remote learning in March 2020 were new. But they highlighted a divide that had been there all along in another form: homework. And even long after schools have resumed in-person classes, the pandemic’s effects on homework have lingered.

Over the past three years, in response to concerns about equity, schools across the country, including in Sacramento, Los Angeles , San Diego , and Clark County, Nevada , made permanent changes to their homework policies that restricted how much homework could be given and how it could be graded after in-person learning resumed.

Three years into the pandemic, as districts and teachers reckon with Covid-era overhauls of teaching and learning, schools are still reconsidering the purpose and place of homework. Whether relaxing homework expectations helps level the playing field between students or harms them by decreasing rigor is a divisive issue without conclusive evidence on either side, echoing other debates in education like the elimination of standardized test scores from some colleges’ admissions processes.

I first began to wonder if the homework abolition movement made sense after speaking with teachers in some Massachusetts public schools, who argued that rather than help disadvantaged kids, stringent homework restrictions communicated an attitude of low expectations. One, an English teacher, said she felt the school had “just given up” on trying to get the students to do work; another argued that restrictions that prohibit teachers from assigning take-home work that doesn’t begin in class made it difficult to get through the foreign-language curriculum. Teachers in other districts have raised formal concerns about homework abolition’s ability to close gaps among students rather than widening them.

Many education experts share this view. Harris Cooper, a professor emeritus of psychology at Duke who has studied homework efficacy, likened homework abolition to “playing to the lowest common denominator.”

But as I learned after talking to a variety of stakeholders — from homework researchers to policymakers to parents of schoolchildren — whether to abolish homework probably isn’t the right question. More important is what kind of work students are sent home with and where they can complete it. Chances are, if schools think more deeply about giving constructive work, time spent on homework will come down regardless.

There’s no consensus on whether homework works

The rise of the no-homework movement during the Covid-19 pandemic tapped into long-running disagreements over homework’s impact on students. The purpose and effectiveness of homework have been disputed for well over a century. In 1901, for instance, California banned homework for students up to age 15, and limited it for older students, over concerns that it endangered children’s mental and physical health. The newest iteration of the anti-homework argument contends that the current practice punishes students who lack support and rewards those with more resources, reinforcing the “myth of meritocracy.”

But there is still no research consensus on homework’s effectiveness; no one can seem to agree on what the right metrics are. Much of the debate relies on anecdotes, intuition, or speculation.

Researchers disagree even on how much research exists on the value of homework. Kathleen Budge, the co-author of Turning High-Poverty Schools Into High-Performing Schools and a professor at Boise State, told me that homework “has been greatly researched.” Denise Pope, a Stanford lecturer and leader of the education nonprofit Challenge Success, said, “It’s not a highly researched area because of some of the methodological problems.”

Experts who are more sympathetic to take-home assignments generally support the “10-minute rule,” a framework that estimates the ideal amount of homework on any given night by multiplying the student’s grade by 10 minutes. (A ninth grader, for example, would have about 90 minutes of work a night.) Homework proponents argue that while it is difficult to design randomized control studies to test homework’s effectiveness, the vast majority of existing studies show a strong positive correlation between homework and high academic achievement for middle and high school students. Prominent critics of homework argue that these correlational studies are unreliable and point to studies that suggest a neutral or negative effect on student performance. Both agree there is little to no evidence for homework’s effectiveness at an elementary school level, though proponents often argue that it builds constructive habits for the future.

For anyone who remembers homework assignments from both good and bad teachers, this fundamental disagreement might not be surprising. Some homework is pointless and frustrating to complete. Every week during my senior year of high school, I had to analyze a poem for English and decorate it with images found on Google; my most distinct memory from that class is receiving a demoralizing 25-point deduction because I failed to present my analysis on a poster board. Other assignments really do help students learn: After making an adapted version of Chairman Mao’s Little Red Book for a ninth grade history project, I was inspired to check out from the library and read a biography of the Chinese ruler.

For homework opponents, the first example is more likely to resonate. “We’re all familiar with the negative effects of homework: stress, exhaustion, family conflict, less time for other activities, diminished interest in learning,” Alfie Kohn, author of The Homework Myth, which challenges common justifications for homework, told me in an email. “And these effects may be most pronounced among low-income students.” Kohn believes that schools should make permanent any moratoria implemented during the pandemic, arguing that there are no positives at all to outweigh homework’s downsides. Recent studies , he argues , show the benefits may not even materialize during high school.

In the Marlborough Public Schools, a suburban district 45 minutes west of Boston, school policy committee chair Katherine Hennessy described getting kids to complete their homework during remote education as “a challenge, to say the least.” Teachers found that students who spent all day on their computers didn’t want to spend more time online when the day was over. So, for a few months, the school relaxed the usual practice and teachers slashed the quantity of nightly homework.

Online learning made the preexisting divides between students more apparent, she said. Many students, even during normal circumstances, lacked resources to keep them on track and focused on completing take-home assignments. Though Marlborough Schools is more affluent than PS 55, Hennessy said many students had parents whose work schedules left them unable to provide homework help in the evenings. The experience tracked with a common divide in the country between children of different socioeconomic backgrounds.

So in October 2021, months after the homework reduction began, the Marlborough committee made a change to the district’s policy. While teachers could still give homework, the assignments had to begin as classwork. And though teachers could acknowledge homework completion in a student’s participation grade, they couldn’t count homework as its own grading category. “Rigorous learning in the classroom does not mean that that classwork must be assigned every night,” the policy stated . “Extensions of class work is not to be used to teach new content or as a form of punishment.”

Canceling homework might not do anything for the achievement gap

The critiques of homework are valid as far as they go, but at a certain point, arguments against homework can defy the commonsense idea that to retain what they’re learning, students need to practice it.

“Doesn’t a kid become a better reader if he reads more? Doesn’t a kid learn his math facts better if he practices them?” said Cathy Vatterott, an education researcher and professor emeritus at the University of Missouri-St. Louis. After decades of research, she said it’s still hard to isolate the value of homework, but that doesn’t mean it should be abandoned.

Blanket vilification of homework can also conflate the unique challenges facing disadvantaged students as compared to affluent ones, which could have different solutions. “The kids in the low-income schools are being hurt because they’re being graded, unfairly, on time they just don’t have to do this stuff,” Pope told me. “And they’re still being held accountable for turning in assignments, whether they’re meaningful or not.” On the other side, “Palo Alto kids” — students in Silicon Valley’s stereotypically pressure-cooker public schools — “are just bombarded and overloaded and trying to stay above water.”

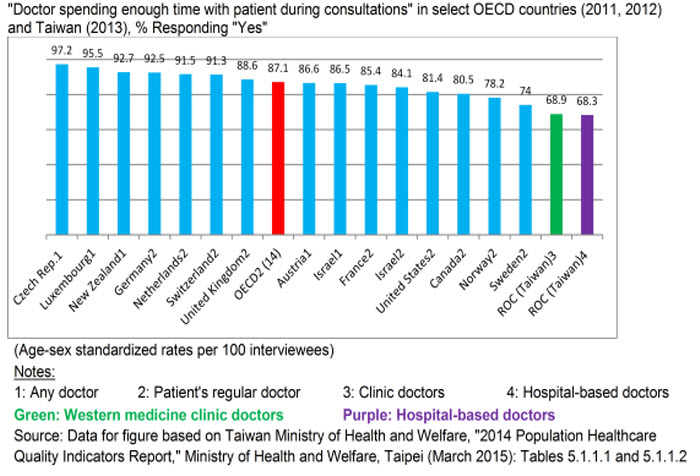

Merely getting rid of homework doesn’t solve either problem. The United States already has the second-highest disparity among OECD (the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) nations between time spent on homework by students of high and low socioeconomic status — a difference of more than three hours, said Janine Bempechat, clinical professor at Boston University and author of No More Mindless Homework .

When she interviewed teachers in Boston-area schools that had cut homework before the pandemic, Bempechat told me, “What they saw immediately was parents who could afford it immediately enrolled their children in the Russian School of Mathematics,” a math-enrichment program whose tuition ranges from $140 to about $400 a month. Getting rid of homework “does nothing for equity; it increases the opportunity gap between wealthier and less wealthy families,” she said. “That solution troubles me because it’s no solution at all.”

A group of teachers at Wakefield High School in Arlington, Virginia, made the same point after the school district proposed an overhaul of its homework policies, including removing penalties for missing homework deadlines, allowing unlimited retakes, and prohibiting grading of homework.

“Given the emphasis on equity in today’s education systems,” they wrote in a letter to the school board, “we believe that some of the proposed changes will actually have a detrimental impact towards achieving this goal. Families that have means could still provide challenging and engaging academic experiences for their children and will continue to do so, especially if their children are not experiencing expected rigor in the classroom.” At a school where more than a third of students are low-income, the teachers argued, the policies would prompt students “to expect the least of themselves in terms of effort, results, and responsibility.”

Not all homework is created equal

Despite their opposing sides in the homework wars, most of the researchers I spoke to made a lot of the same points. Both Bempechat and Pope were quick to bring up how parents and schools confuse rigor with workload, treating the volume of assignments as a proxy for quality of learning. Bempechat, who is known for defending homework, has written extensively about how plenty of it lacks clear purpose, requires the purchasing of unnecessary supplies, and takes longer than it needs to. Likewise, when Pope instructs graduate-level classes on curriculum, she asks her students to think about the larger purpose they’re trying to achieve with homework: If they can get the job done in the classroom, there’s no point in sending home more work.

At its best, pandemic-era teaching facilitated that last approach. Honolulu-based teacher Christina Torres Cawdery told me that, early in the pandemic, she often had a cohort of kids in her classroom for four hours straight, as her school tried to avoid too much commingling. She couldn’t lecture for four hours, so she gave the students plenty of time to complete independent and project-based work. At the end of most school days, she didn’t feel the need to send them home with more to do.

A similar limited-homework philosophy worked at a public middle school in Chelsea, Massachusetts. A couple of teachers there turned as much class as possible into an opportunity for small-group practice, allowing kids to work on problems that traditionally would be assigned for homework, Jessica Flick, a math coach who leads department meetings at the school, told me. It was inspired by a philosophy pioneered by Simon Fraser University professor Peter Liljedahl, whose influential book Building Thinking Classrooms in Mathematics reframes homework as “check-your-understanding questions” rather than as compulsory work. Last year, Flick found that the two eighth grade classes whose teachers adopted this strategy performed the best on state tests, and this year, she has encouraged other teachers to implement it.

Teachers know that plenty of homework is tedious and unproductive. Jeannemarie Dawson De Quiroz, who has taught for more than 20 years in low-income Boston and Los Angeles pilot and charter schools, says that in her first years on the job she frequently assigned “drill and kill” tasks and questions that she now feels unfairly stumped students. She said designing good homework wasn’t part of her teaching programs, nor was it meaningfully discussed in professional development. With more experience, she turned as much class time as she could into practice time and limited what she sent home.

“The thing about homework that’s sticky is that not all homework is created equal,” says Jill Harrison Berg, a former teacher and the author of Uprooting Instructional Inequity . “Some homework is a genuine waste of time and requires lots of resources for no good reason. And other homework is really useful.”

Cutting homework has to be part of a larger strategy

The takeaways are clear: Schools can make cuts to homework, but those cuts should be part of a strategy to improve the quality of education for all students. If the point of homework was to provide more practice, districts should think about how students can make it up during class — or offer time during or after school for students to seek help from teachers. If it was to move the curriculum along, it’s worth considering whether strategies like Liljedahl’s can get more done in less time.

Some of the best thinking around effective assignments comes from those most critical of the current practice. Denise Pope proposes that, before assigning homework, teachers should consider whether students understand the purpose of the work and whether they can do it without help. If teachers think it’s something that can’t be done in class, they should be mindful of how much time it should take and the feedback they should provide. It’s questions like these that De Quiroz considered before reducing the volume of work she sent home.

More than a year after the new homework policy began in Marlborough, Hennessy still hears from parents who incorrectly “think homework isn’t happening” despite repeated assurances that kids still can receive work. She thinks part of the reason is that education has changed over the years. “I think what we’re trying to do is establish that homework may be an element of educating students,” she told me. “But it may not be what parents think of as what they grew up with. ... It’s going to need to adapt, per the teaching and the curriculum, and how it’s being delivered in each classroom.”

For the policy to work, faculty, parents, and students will all have to buy into a shared vision of what school ought to look like. The district is working on it — in November, it hosted and uploaded to YouTube a round-table discussion on homework between district administrators — but considering the sustained confusion, the path ahead seems difficult.

When I asked Luis Torres about whether he thought homework serves a useful part in PS 55’s curriculum, he said yes, of course it was — despite the effort and money it takes to keep the school open after hours to help them do it. “The children need the opportunity to practice,” he said. “If you don’t give them opportunities to practice what they learn, they’re going to forget.” But Torres doesn’t care if the work is done at home. The school stays open until around 6 pm on weekdays, even during breaks. Tutors through New York City’s Department of Youth and Community Development programs help kids with work after school so they don’t need to take it with them.

As schools weigh the purpose of homework in an unequal world, it’s tempting to dispose of a practice that presents real, practical problems to students across the country. But getting rid of homework is unlikely to do much good on its own. Before cutting it, it’s worth thinking about what good assignments are meant to do in the first place. It’s crucial that students from all socioeconomic backgrounds tackle complex quantitative problems and hone their reading and writing skills. It’s less important that the work comes home with them.

Jacob Sweet is a freelance writer in Somerville, Massachusetts. He is a frequent contributor to the New Yorker, among other publications.

Will you help keep Vox free for all?

Millions rely on Vox’s journalism to understand the coronavirus crisis. We believe it pays off for all of us, as a society and a democracy, when our neighbors and fellow citizens can access clear, concise information on the pandemic. But our distinctive explanatory journalism is expensive. Support from our readers helps us keep it free for everyone. If you have already made a financial contribution to Vox, thank you. If not, please consider making a contribution today from as little as $3.

We accept credit card, Apple Pay, and Google Pay. You can also contribute via

Want financial security in America? Better get married.

A utopian strand of economic thought is making a surprising comeback, alcohol overuse causes 178,000 american deaths annually. why is it so undertreated, sign up for the newsletter today, explained, thanks for signing up.

Check your inbox for a welcome email.

Oops. Something went wrong. Please enter a valid email and try again.

Origin and Death of Homework Inventor: Roberto Nevilis

Roberto Nevilis is known for creating homework to help students learn on their own. He was a teacher who introduced the idea of giving assignments to be done outside of class. Even though there’s some debate about his exact role, Nevilis has left a lasting impact on education, shaping the way students around the world approach their studies.

Homework is a staple of the modern education system, but few people know the story of its origin.

The inventor of homework is widely considered to be Roberto Nevilis, an Italian educator who lived in the early 20th century.

We will briefly explore Nevilis’ life, how he came up with the concept of homework, and the circumstances surrounding his death.

Roberto Nevilis: The Man Behind Homework Roberto Nevilis was born in Venice, Italy, in 1879. He was the son of a wealthy merchant and received a private education.

He later studied at the University of Venice, where he received a degree in education. After graduation, Nevilis worked as a teacher in various schools in Venice.

Table of Contents

How Homework Was Born

The Birth of Homework According to historical records, Nevilis was frustrated with the lack of discipline in his classroom. He found that students were often too focused on playing and not enough on learning.

To solve this problem , he came up with the concept of homework. Nevilis assigned his students homework to reinforce the lessons they learned in class and encourage them to take their education more seriously.

How did homework become popular?

The Spread of Homework , The idea of homework quickly caught on, and soon other teachers in Italy followed Nevilis’ lead. From Italy, the practice of assigning homework spread to other European countries and, eventually, the rest of the world.

Today, homework is a standard part of the education system in almost every country, and millions of students worldwide spend countless hours each week working on homework assignments.

How did Roberto Nevilis Die?

Death of Roberto Nevilis The exact circumstances surrounding Nevilis’ death are unknown. Some reports suggest that he died in an accident, while others claim he was murdered.

However, the lack of concrete evidence has led to numerous theories and speculation about what happened to the inventor of homework.

Despite the mystery surrounding his death, Nevilis’ legacy lives on through his impact on education.

Facts about Roberto Nevilis

- He is credited with inventing homework to punish his students who misbehaved in class.

- Some accounts suggest he was a strict teacher who believed in disciplining his students with homework.

- There is little concrete evidence to support the claim that Nevilis was the true inventor of homework.

- Some historians believe that the concept of homework has been around for much longer than in the 1900s.

- Despite the lack of evidence, Roberto Nevilis remains a popular figure in the history of education and is often cited as the inventor of homework.

The Legacy of Homework

The legacy of homework is deeply embedded in the educational landscape, reflecting a historical evolution that spans centuries. From its ambiguous origins to the diverse purposes it serves today, homework has played a pivotal role in shaping learning experiences.

While its effectiveness and necessity have been subjects of ongoing debate, homework endures as a tool for reinforcing concepts, fostering independent study habits, and preparing students for future academic and professional challenges.

In the contemporary educational context, the legacy of homework is a complex interplay of tradition, pedagogy, and evolving perspectives on the balance between academic demands and student well-being.

The Complex History of Homework

Throughout history, the evolution of homework can be traced through a series of significant developments. In ancient civilizations, such as Greece and Rome, scholars and philosophers encouraged independent study outside formal learning settings.

The Renaissance era witnessed a surge in written assignments, marking an early precursor to modern homework. The Industrial Revolution further transformed educational practices, as the need for a skilled workforce emphasized the importance of individual learning and practice.

The purposes and perceptions of homework have undergone substantial transformations over time. In the 19th century, homework was often viewed as a means of reinforcing discipline and moral values, with assignments focused on character development.

As educational philosophies evolved, particularly in the 20th century, homework assumed various roles—from a tool for drill and practice to a method for fostering critical thinking and problem-solving skills.

Perceptions of homework have fluctuated, with debates arising around issues of workload, equity, and its impact on student well-being. The complex history of homework reveals a dynamic interplay between societal expectations, educational philosophies, and changing perspectives on the purposes of academic assignments.

Conclusion – Who invented homework, and how did he die

Roberto Nevilis was a visionary educator who profoundly impacted the education system. His invention of homework has changed how students learn and has helped countless students worldwide improve their education.

Although the circumstances surrounding his death are unclear, Nevilis’ legacy as the inventor of homework will never be forgotten.

What is Roberto Nevilis’ legacy?

Roberto Nevilis’ legacy is his invention of homework, which has changed how students learn and has helped countless students worldwide improve their education.

Despite the mystery surrounding his death, Nevilis’ legacy as the inventor of homework will never be forgotten.

What was Roberto Nevilis’ background?

Roberto Nevilis was the son of a wealthy merchant and received a private education. He later studied at the University of Venice, where he received a degree in education.

After graduation, Nevilis worked as a teacher in various schools in Venice.

What was Roberto Nevilis’ impact on education?

Roberto Nevilis’ invention of homework has had a profound impact on education. By assigning homework, he helped students reinforce the lessons they learned in class and encouraged them to take their education more seriously.

This concept has spread worldwide and is now a staple of the modern education system.

Is there any evidence to support the theories about Roberto Nevilis’ death?

There is no concrete evidence to support the theories about Roberto Nevilis’ death, and the exact circumstances surrounding his death remain a mystery.

What was Roberto nevilis age?

It is believed that he died of old age. Not much information is available on his exact age at the time of death.

Where is Roberto Nevilis’s grave

While many have tried to find out about his Grave, little is known about where he is buried. Many people are querying the internet about his Grave. But frankly, I find it weird why people want to know this.

Share this:

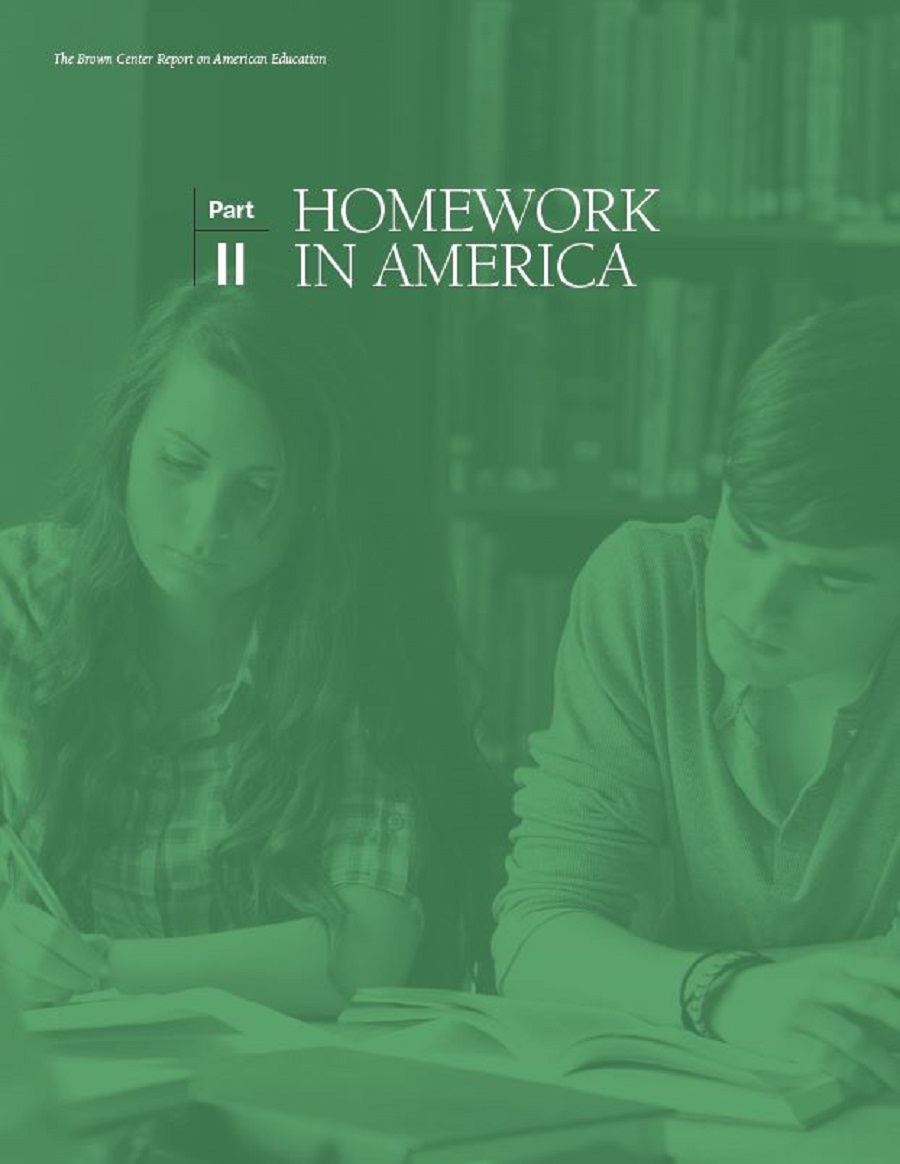

Homework in America

- 2014 Brown Center Report on American Education

Subscribe to the Brown Center on Education Policy Newsletter

Tom loveless tom loveless former brookings expert @tomloveless99.

March 18, 2014

- 18 min read

Part II of the 2014 Brown Center Report on American Education

Homework! The topic, no, just the word itself, sparks controversy. It has for a long time. In 1900, Edward Bok, editor of the Ladies Home Journal , published an impassioned article, “A National Crime at the Feet of Parents,” accusing homework of destroying American youth. Drawing on the theories of his fellow educational progressive, psychologist G. Stanley Hall (who has since been largely discredited), Bok argued that study at home interfered with children’s natural inclination towards play and free movement, threatened children’s physical and mental health, and usurped the right of parents to decide activities in the home.

The Journal was an influential magazine, especially with parents. An anti-homework campaign burst forth that grew into a national crusade. [i] School districts across the land passed restrictions on homework, culminating in a 1901 statewide prohibition of homework in California for any student under the age of 15. The crusade would remain powerful through 1913, before a world war and other concerns bumped it from the spotlight. Nevertheless, anti-homework sentiment would remain a touchstone of progressive education throughout the twentieth century. As a political force, it would lie dormant for years before bubbling up to mobilize proponents of free play and “the whole child.” Advocates would, if educators did not comply, seek to impose homework restrictions through policy making.

Our own century dawned during a surge of anti-homework sentiment. From 1998 to 2003, Newsweek , TIME , and People , all major national publications at the time, ran cover stories on the evils of homework. TIME ’s 1999 story had the most provocative title, “The Homework Ate My Family: Kids Are Dazed, Parents Are Stressed, Why Piling On Is Hurting Students.” People ’s 2003 article offered a call to arms: “Overbooked: Four Hours of Homework for a Third Grader? Exhausted Kids (and Parents) Fight Back.” Feature stories about students laboring under an onerous homework burden ran in newspapers from coast to coast. Photos of angst ridden children became a journalistic staple.

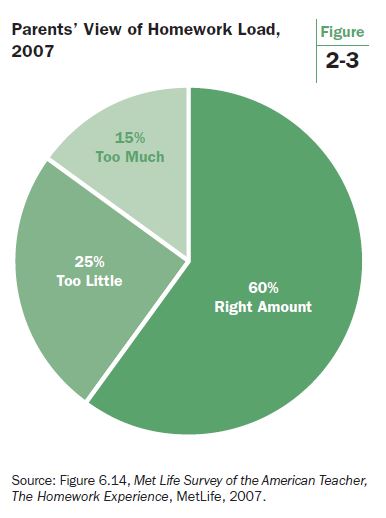

The 2003 Brown Center Report on American Education included a study investigating the homework controversy. Examining the most reliable empirical evidence at the time, the study concluded that the dramatic claims about homework were unfounded. An overwhelming majority of students, at least two-thirds, depending on age, had an hour or less of homework each night. Surprisingly, even the homework burden of college-bound high school seniors was discovered to be rather light, less than an hour per night or six hours per week. Public opinion polls also contradicted the prevailing story. Parents were not up in arms about homework. Most said their children’s homework load was about right. Parents wanting more homework out-numbered those who wanted less.

Now homework is in the news again. Several popular anti-homework books fill store shelves (whether virtual or brick and mortar). [ii] The documentary Race to Nowhere depicts homework as one aspect of an overwrought, pressure-cooker school system that constantly pushes students to perform and destroys their love of learning. The film’s website claims over 6,000 screenings in more than 30 countries. In 2011, the New York Times ran a front page article about the homework restrictions adopted by schools in Galloway, NJ, describing “a wave of districts across the nation trying to remake homework amid concerns that high stakes testing and competition for college have fueled a nightly grind that is stressing out children and depriving them of play and rest, yet doing little to raise achievement, especially in elementary grades.” In the article, Vicki Abeles, the director of Race to Nowhere , invokes the indictment of homework lodged a century ago, declaring, “The presence of homework is negatively affecting the health of our young people and the quality of family time.” [iii]

A petition for the National PTA to adopt “healthy homework guidelines” on change.org currently has 19,000 signatures. In September 2013, Atlantic featured an article, “My Daughter’s Homework is Killing Me,” by a Manhattan writer who joined his middle school daughter in doing her homework for a week. Most nights the homework took more than three hours to complete.

The Current Study

A decade has passed since the last Brown Center Report study of homework, and it’s time for an update. How much homework do American students have today? Has the homework burden increased, gone down, or remained about the same? What do parents think about the homework load?

A word on why such a study is important. It’s not because the popular press is creating a fiction. The press accounts are built on the testimony of real students and real parents, people who are very unhappy with the amount of homework coming home from school. These unhappy people are real—but they also may be atypical. Their experiences, as dramatic as they are, may not represent the common experience of American households with school-age children. In the analysis below, data are analyzed from surveys that are methodologically designed to produce reliable information about the experiences of all Americans. Some of the surveys have existed long enough to illustrate meaningful trends. The question is whether strong empirical evidence confirms the anecdotes about overworked kids and outraged parents.

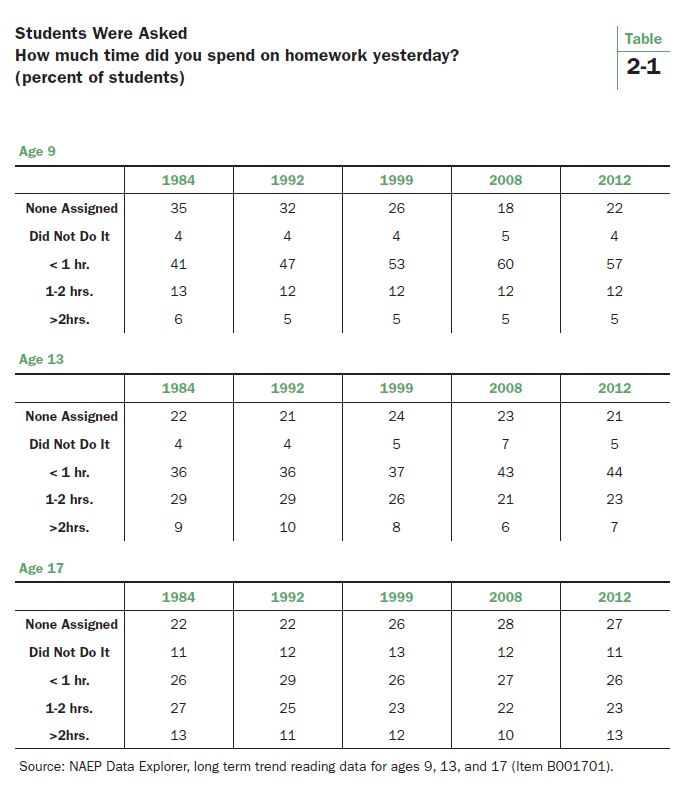

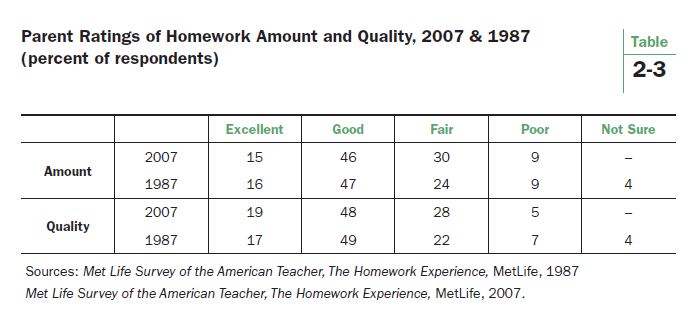

Data from the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) provide a good look at trends in homework for nearly the past three decades. Table 2-1 displays NAEP data from 1984-2012. The data are from the long-term trend NAEP assessment’s student questionnaire, a survey of homework practices featuring both consistently-worded questions and stable response categories. The question asks: “How much time did you spend on homework yesterday?” Responses are shown for NAEP’s three age groups: 9, 13, and 17. [iv]

Today’s youngest students seem to have more homework than in the past. The first three rows of data for age 9 reveal a shift away from students having no homework, declining from 35% in 1984 to 22% in 2012. A slight uptick occurred from the low of 18% in 2008, however, so the trend may be abating. The decline of the “no homework” group is matched by growth in the percentage of students with less than an hour’s worth, from 41% in 1984 to 57% in 2012. The share of students with one to two hours of homework changed very little over the entire 28 years, comprising 12% of students in 2012. The group with the heaviest load, more than two hours of homework, registered at 5% in 2012. It was 6% in 1984.

The amount of homework for 13-year-olds appears to have lightened slightly. Students with one to two hours of homework declined from 29% to 23%. The next category down (in terms of homework load), students with less than an hour, increased from 36% to 44%. One can see, by combining the bottom two rows, that students with an hour or more of homework declined steadily from 1984 to 2008 (falling from 38% to 27%) and then ticked up to 30% in 2012. The proportion of students with the heaviest load, more than two hours, slipped from 9% in 1984 to 7% in 2012 and ranged between 7-10% for the entire period.

For 17-year-olds, the homework burden has not varied much. The percentage of students with no homework has increased from 22% to 27%. Most of that gain occurred in the 1990s. Also note that the percentage of 17-year-olds who had homework but did not do it was 11% in 2012, the highest for the three NAEP age groups. Adding that number in with the students who didn’t have homework in the first place means that more than one-third of seventeen year olds (38%) did no homework on the night in question in 2012. That compares with 33% in 1984. The segment of the 17-year-old population with more than two hours of homework, from which legitimate complaints of being overworked might arise, has been stuck in the 10%-13% range.

The NAEP data point to four main conclusions:

- With one exception, the homework load has remained remarkably stable since 1984.

- The exception is nine-year-olds. They have experienced an increase in homework, primarily because many students who once did not have any now have some. The percentage of nine-year-olds with no homework fell by 13 percentage points, and the percentage with less than an hour grew by 16 percentage points.

- Of the three age groups, 17-year-olds have the most bifurcated distribution of the homework burden. They have the largest percentage of kids with no homework (especially when the homework shirkers are added in) and the largest percentage with more than two hours.

- NAEP data do not support the idea that a large and growing number of students have an onerous amount of homework. For all three age groups, only a small percentage of students report more than two hours of homework. For 1984-2012, the size of the two hours or more groups ranged from 5-6% for age 9, 6-10% for age 13, and 10-13% for age 17.

Note that the item asks students how much time they spent on homework “yesterday.” That phrasing has the benefit of immediacy, asking for an estimate of precise, recent behavior rather than an estimate of general behavior for an extended, unspecified period. But misleading responses could be generated if teachers lighten the homework of NAEP participants on the night before the NAEP test is given. That’s possible. [v] Such skewing would not affect trends if it stayed about the same over time and in the same direction (teachers assigning less homework than usual on the day before NAEP). Put another way, it would affect estimates of the amount of homework at any single point in time but not changes in the amount of homework between two points in time.

A check for possible skewing is to compare the responses above with those to another homework question on the NAEP questionnaire from 1986-2004 but no longer in use. [vi] It asked students, “How much time do you usually spend on homework each day?” Most of the response categories have different boundaries from the “last night” question, making the data incomparable. But the categories asking about no homework are comparable. Responses indicating no homework on the “usual” question in 2004 were: 2% for age 9-year-olds, 5% for 13 year olds, and 12% for 17-year-olds. These figures are much less than the ones reported in Table 2-1 above. The “yesterday” data appear to overstate the proportion of students typically receiving no homework.

The story is different for the “heavy homework load” response categories. The “usual” question reported similar percentages as the “yesterday” question. The categories representing the most amount of homework were “more than one hour” for age 9 and “more than two hours” for ages 13 and 17. In 2004, 12% of 9-year-olds said they had more than one hour of daily homework, while 8% of 13-year-olds and 12% of 17-year-olds said they had more than two hours. For all three age groups, those figures declined from1986 to 2004. The decline for age 17 was quite large, falling from 17% in 1986 to 12% in 2004.

The bottom line: regardless of how the question is posed, NAEP data do not support the view that the homework burden is growing, nor do they support the belief that the proportion of students with a lot of homework has increased in recent years. The proportion of students with no homework is probably under-reported on the long-term trend NAEP. But the upper bound of students with more than two hours of daily homework appears to be about 15%–and that is for students in their final years of high school.

College Freshmen Look Back

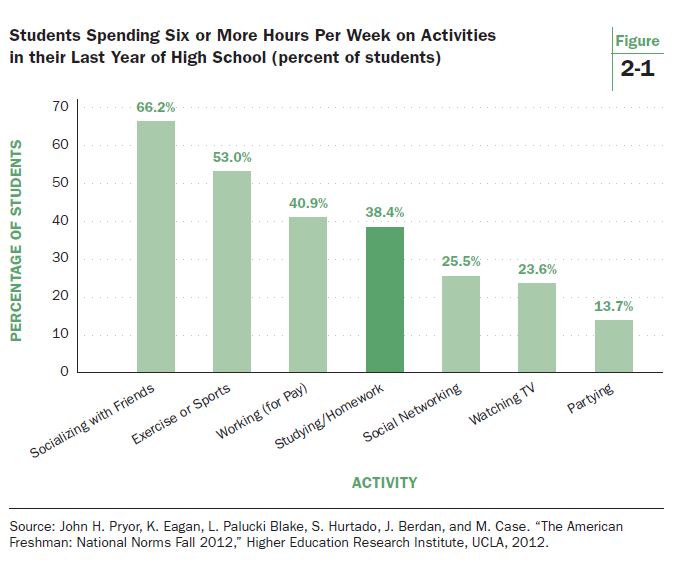

There is another good source of information on high school students’ homework over several decades. The Higher Education Research Institute at UCLA conducts an annual survey of college freshmen that began in 1966. In 1986, the survey started asking a series of questions regarding how students spent time in the final year of high school. Figure 2-1 shows the 2012 percentages for the dominant activities. More than half of college freshmen say they spent at least six hours per week socializing with friends (66.2%) and exercising/sports (53.0%). About 40% devoted that much weekly time to paid employment.

Homework comes in fourth pace. Only 38.4% of students said they spent at least six hours per week studying or doing homework. When these students were high school seniors, it was not an activity central to their out of school lives. That is quite surprising. Think about it. The survey is confined to the nation’s best students, those attending college. Gone are high school dropouts. Also not included are students who go into the military or attain full time employment immediately after high school. And yet only a little more than one-third of the sampled students, devoted more than six hours per week to homework and studying when they were on the verge of attending college.

Another notable finding from the UCLA survey is how the statistic is trending (see Figure 2-2). In 1986, 49.5% reported spending six or more hours per week studying and doing homework. By 2002, the proportion had dropped to 33.4%. In 2012, as noted in Figure 2-1, the statistic had bounced off the historical lows to reach 38.4%. It is slowly rising but still sits sharply below where it was in 1987.

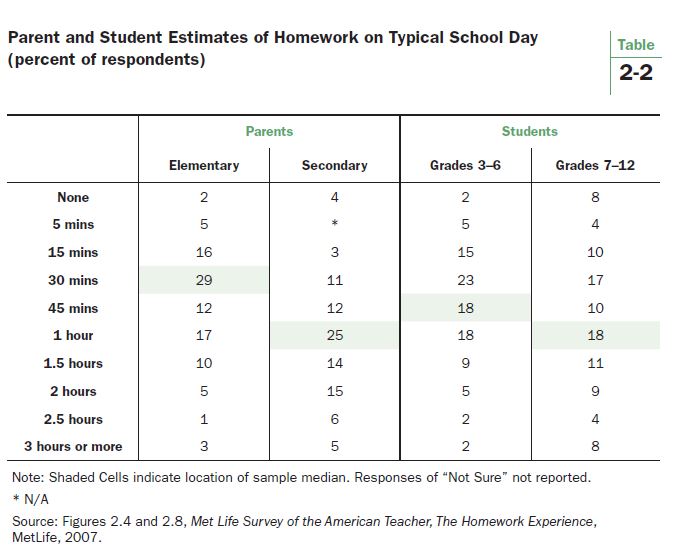

What Do Parents Think?