The future of healthcare: Value creation through next-generation business models

The healthcare industry in the United States has experienced steady growth over the past decade while simultaneously promoting quality, efficiency, and access to care. Between 2012 and 2019, profit pools (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization, or EBITDA) grew at a compound average growth rate of roughly 5 percent. This growth was aided in part by incremental healthcare spending that resulted from the 2010 Affordable Care Act. In 2020, subsidies for qualified individual purchasers on the marketplaces and expansion of Medicaid coverage resulted in roughly $130 billion 1 Federal Subsidies for Health Insurance Coverage for People Under Age 65: CBO and JCT’s March 2020 Projections, Congressional Budget Office, Washington, DC, September 29, 2020, cbo.gov. 2 Includes adults made eligible for Medicaid by the ACA and marketplace-related coverage and the Basic Health Program. of incremental healthcare spending by the federal government.

The next three years are expected to be less positive for the economics of the healthcare industry, as profit pools are more likely to be flat. COVID-19 has led to the potential for economic headwinds and a rebalancing of system funds. Current unemployment rates (6.9 percent as of October 2020) 3 The employment situation—October 2020 , US Department of Labor, November 6, 2020, bls.gov. indicate some individuals may move from employer-sponsored insurance to other options. It is expected that roughly between $70 billion and $100 billion in funding may leave the healthcare system by 2022, compared with the expected trajectory pre-COVID-19. The outflow is driven by coverage shifts out of employer-sponsored insurance, product buy-downs, and Medicaid rate pressures from states, partially offset by increased federal spending in the form of subsidies and cost sharing in the Individual market and in Medicaid funding.

Underlying this broader outlook are chances to innovate (Exhibit 1). 4 Smit S, Hirt M, Buehler K, Lund S, Greenberg E, and Govindarajan A, “ Safeguarding our lives and our livelihoods: The imperative of our time ,” March 23, 2020, McKinsey.com. Innovation may drive outpaced growth in three categories: segments that are anticipated to rebound from poor performance over recent years, segments that benefit from shifting care patterns that result directly from COVID-19, and segments where growth was expected pre-COVID-19 and remain largely unaffected by the pandemic. For the payer vertical, we estimate profit pools in Medicaid will likely increase by more than 10 percent per annum from 2019 to 2022 as a result of increased enrollment and normalized margins following historical lows. In the provider vertical, the rapid acceleration in the use of telehealth and other virtual care options spurred by COVID-19 could continue. 5 Bestsennyy O, Gilbert G, Harris A, and Rost J, “ Telehealth: A quarter-trillion-dollar post-COVID-19 reality? ” May 29, 2020, McKinsey.com. Growth is expected across a range of sub-segments in the services and technology vertical, as specialized players are able to provide services at scale (for example, software and platforms and data and analytics). Specialty pharmacy is another area where strong growth in profit pools is likely, with between 5 and 10 percent compound annual growth rate (CAGR) expected in infusion services and hospital-owned specialty pharmacy sub-segments.

Strategies that align to attractive and growing profit pools, while important, may be insufficient to achieve the growth that incumbents have come to expect. For example, in 2019, 34 percent of all revenue in the healthcare system was linked to a profit pool that grew at greater than 5 percent per year (from 2017 to 2019). In contrast, we estimate that only 13 percent of revenue in 2022 will be linked to profit pools growing at that rate between 2019 and 2022. This estimate reflects that profit pools are growing more slowly due to factors that include lower membership growth, margin pressure, and lower revenue growth. This relative scarcity in opportunity could lead to increased competition in attractive sub-segments with the potential for profits to be spread thinly across organizations. Developing new and innovative business models will become important to achieve the level of EBITDA growth observed in recent years and deliver better care for individuals. The good news is that there is significant opportunity, and need, for innovation in healthcare.

New and innovative business models across verticals can generate greater value and deliver better care for individuals

Glimpse into profit pool analyses and select sub-segments.

Within the context of these overarching observations, the projections for specific sub-segments are nuanced and tightly connected to the specific dynamics each sub-segment is currently facing:

- Payer—Small Group: Small group has historically seen membership declines and we expect this trend to continue and/or accelerate in the event of an economic downturn. Membership declines will increase competition and put pressure on incumbent market leaders to both maintain share and margin as membership declines, but fixed costs remain.

- Payer—Medicare Advantage: Historic profit pool growth in the Medicare Advantage space has been driven by enrollment gains that result from demographic trends and a long-term trend of seniors moving from traditional Medicare fee-for-service programs to Medicare Advantage plans that have increasingly offered attractive ancillary benefits (for example, dental benefits, gym memberships). Going forward, we expect Medicare members to be relatively insulated from the effects of an economic downturn that will impact employers and individuals in other payer segments.

- Provider—General acute care hospitals: Cancelation of elective procedures due to COVID-19 is expected to lead to volume and revenue reductions in 2019 and 2020. Though volume is expected to recover partially by 2022, growth will likely be slowed due to the accelerated shift from hospitals to virtual care and other non-acute settings. Payer mix shifts from employer-sponsored to Medicaid and uninsured populations in 2020 and 2021 are also likely to exert downward pressure on hospital revenue and EBITDA, possibly driving cost-optimization measures through 2022.

- Provider—Independent labs: COVID-19 testing is expected to drive higher than average utilization growth in independent labs through 2020 and 2021, with more typical utilization returning by 2022. However, labs may experience pressure on revenue and EBITDA growth as the payer mix shifts to lower-margin segments, offsetting some of the gains attributed to utilization.

- Provider—Virtual office visits: Telehealth has helped expand access to care at a time when the pandemic has restricted patients’ ability to see providers in person. Consumer adoption and stickiness, along with providers’ push to scale-up telehealth offerings, are expected to lead to more than 100 percent growth per annum in the segment from 2019 to 2022, going beyond traditional “tele-urgent” to more comprehensive virtual care.

- HST—Medical financing: The medical financing segment may be negatively impacted in 2020 due to COVID-19, as many elective services for which financing is used have been deferred. However, a quick bounce-back is expected as more patients lacking healthcare coverage may need financing in 2021, and as providers may use medical financing as a lever to improve cash reserves.

- HST—Wearables: Looking ahead, the wearables segment is expected to see a slight dip in 2020 due to COVID-19, but is expected to rebound in 2021 and 2022 given consumer interest in personal wellness and for tracking health indicators.

- Pharma services—Pharmacy benefit management: The growth is expected to return to baseline expectations by 2022 after an initial decline in 2020 and 2021 due to the COVID-19-driven decrease in prescription volume.

New and innovative business models are beginning to show promise in delivering better care and generating higher returns. The existence of these models and their initial successes are reflective of what we have observed in the market in recent years: leading organizations in the healthcare industry are not content to simply play in attractive segments and markets, but instead are proactively and fundamentally reshaping how the industry operates and how care is delivered. While the recipe across verticals varies, common among these new business models are greater alignment of incentives typically involving risk bearing, better integration of care, and use of data and advanced analytics.

Payers—Next-generation managed care models

For payers, the new and innovative business models that are generating superior returns are those that incorporate care delivery and advanced analytics to better serve individuals with increasingly complex healthcare needs (Exhibit 2). As chronic disease and other long-term conditions require more continuous management supported by providers (for example, behavioral health conditions), these next-generation managed care models have garnered notice. Nine of the top ten payers have made acquisitions in the care delivery space. Such models intend to reorient the traditional payer model away from an operational focus on financing healthcare and pricing risk, and toward more integrated managed care models that better align incentives and provide higher-quality, better experience, lower-cost, and more accessible care. Payers that deployed next-generation managed care models generate 0.5 percentage points of EBITDA margin above average expectations after normalizing for payer scale, geographical footprint, and segment mix, according to our research.

The evidence for the effectiveness of these next-generation care models goes beyond the financial analysis of returns. We observe that these models are being deployed in those geographies that have the greatest opportunity to positively impact individuals. Those markets with 1) a critical mass of disease burden, 2) presence of compressible costs (the opportunity for care to be redirected to lower-cost settings), and 3) a market structure conducive to shifting to higher-value sites of care, offer substantial ways to improve outcomes and reduce costs. (Exhibit 3).

Currently, a handful of payers—often large national players with access to capital and geographic breadth that enables acquisition of at-scale providers and technologies—have begun to pursue such models. Smaller payers may find it more difficult to make outright acquisitions, given capital constraints and geographic limitations. M&A activity across the care delivery landscape is leaving smaller and more localized assets available for integration and partnership. Payers may need to increasingly turn toward strategic partnerships and alliances to create value and integrate a range of offerings that address all drivers of health.

Providers—reimagining care delivery beyond the hospital

For health systems, through an investment lens, the ownership and integration of alternative sites of care beyond the hospital has demonstrated superior financial returns. Between 2013 and 2018, the number of transactions executed by health systems for outpatient assets increased by 31 percent, for physician practices by 23 percent, and for post-acute care assets by 13 percent. At the same time, the number of hospital-focused deals declined by 6 percent. In addition, private equity investors and payers are becoming more active dealmakers in these non-acute settings. 6 CapitalIQ, Dealogic, and Irving Levin Associates. 7 In 2018, around 40 percent of all post-acute and outpatient deals were completed by an acquirer other than a traditional provider.

As investment is focused on alternative sites of care, we observe that health systems pursuing diversified business models that encompass a greater range of care delivery assets (for example, physician practices, ambulatory surgery centers, and urgent care centers) are generating returns above expectations (Exhibit 4). By offering diverse settings to receive care, many of these systems have been able to lower costs, enhance coordination, and improve patient experience while maintaining or enhancing the quality of the services provided. Consistent with prior research, 8 Singhal S, Latko B, and Pardo Martin C, “ The future of healthcare: Finding the opportunities that lie beneath the uncertainty ,” January 31, 2018, McKinsey.com. systems with high market share tend to outperform peers with lower market share, potentially because systems with greater share have greater ability not only to ensure referral integrity but also to leverage economies of scale that drive efficiency.

The extent of this outperformance, however, varies by market type. For players with top quartile share, the difference in outperformance between acute-focused players and diverse players is less meaningful. Contrastingly, for bottom quartile players, the increase in value provided by presence beyond the acute setting is more significant. While there may be disadvantages for smaller and sub-scale providers, opportunities exist for these players—as well as new entrants and attackers—to succeed by integrating offerings across the care continuum.

These new models and entrants and their non-acute, technology-enabled, and multichannel offerings can offer a different vision of care delivery. Consumer adoption of telehealth has skyrocketed, from 11 percent of US consumers using telehealth in 2019 to 46 percent now using telehealth to replace canceled healthcare visits. Pre-COVID-19, the total annual revenues of US telehealth players were an estimated $3 billion; with the acceleration of consumer and provider adoption and the extension of telehealth beyond virtual urgent care, up to $250 billion of current US healthcare spend could be virtualized. 9 Bestsennyy O, Gilbert G, Harris A, and Rost J, “ Telehealth: A quarter-trillion-dollar post-COVID-19 reality? ” May 29, 2020, McKinsey.com. These early indications suggest that the market may be shifting toward a model of innovative tech-enabled care, one that unlocks value by integrating digital and non-acute settings into a comprehensive, coordinated, and lower-cost offering. While functional care coordination is currently still at the early stages, the potential of technology and other alternative settings raises the question of the role of existing acute-focused providers in a more integrated and digital world.

Would you like to learn more about our Healthcare Systems & Services Practice ?

Healthcare services and technology—innovation and integration across the value chain.

Growth in the healthcare services and technology vertical has been material, as players are bringing technology-enabled services to help improve patient care and boost efficiency. Healthcare services and technology companies are serving nearly all segments of the healthcare ecosystem. These efforts include working with payers and providers to better enable the link between actions and outcomes, to engage with consumers, and to provide real-time and convenient access to health information. Since 2014, a large number and value of deals have been completed: more than 580 deals, or $83 billion in aggregate value. 10 Includes deals over $10 million in value. 11 Analysis from PitchBook Data, Inc. and McKinsey Healthcare Services and Technology domain profit pools model. Venture capital and private equity have fueled much of the innovation in the space: more than 80 percent 12 Includes deals over $10 million in value. of deal volume has come from these institutional investors, while more traditional strategic players have focused on scaling such innovations and integrating them into their core.

Driven by this investment, multiple new models, players, and approaches are emerging across various sub-segments of the technology and services space, driving both innovation (measured by the number of venture capital deals as a percent of total deals) and integration (measured by strategic dollars invested as a percent of total dollars) with traditional payers and providers (Exhibit 5). In some sub-segments, such as data and analytics, utilization management, provider enablement, network management, and clinical information systems, there has been a high rate of both innovation and integration. For instance, in the data and analytics sub-segment, areas such as behavioral health and social determinants of health have driven innovation, while payer and provider investment in at-scale data and analytics platforms has driven deeper integration with existing core platforms. Other sub-segments, such as patient engagement and population health management, have exhibited high innovation but lower integration.

Traditional players have an opportunity to integrate innovative new technologies and offerings to transform and modernize their existing business models. Simultaneously, new (and often non-traditional) players are well positioned to continue to drive innovation across multiple sub-segments and through combinations of capabilities (roll-ups).

Pharmacy value chain—emerging shifts in delivery and management of care

The profit pools within the pharmacy services vertical are shifting from traditional dispensing to specialty pharmacy. Profits earned by retail dispensers (excluding specialty pharmacy) are expected to decline by 0.5 percent per year through 2022, in the face of intensifying competition and the maturing generic market. New modalities of care, new care settings, and new distribution systems are emerging, though many innovations remain in early stages of development.

Specialty pharmacy continues to be an area of outpaced growth. By 2023, specialty pharmacy is expected to account for 44 percent of pharmacy industry prescription revenues, up from 24 percent in 2013. 13 Fein AJ, The 2019 economic report on U.S. pharmacies and pharmacy benefit managers , Drug Channels Institute, 2019, drugchannelsinstitute.com. In response, both incumbents and non-traditional players are seeking opportunities to both capture a rapidly growing portion of the pharmacy value chain and deliver better experience to patients. Health systems, for instance, are increasingly entering the specialty space. Between 2015 and 2018 the share of provider-owned pharmacy locations with specialty pharmacy accreditation more than doubled, from 11 percent in 2015 to 27 percent in 2018, creating an opportunity to directly provide more integrated, holistic care to patients.

Challenges emerge for the US healthcare system as COVID-19 cases rise

A new wave of modalities of care and pharmaceutical innovation are being driven by cell and gene therapies. Global sales are forecasted to grow at more than 40 percent per annum from 2019 to 2024. 14 Evaluate Pharma, February 2020. These new therapies can be potentially curative and often serve patients with high unmet needs, but also pose challenges: 15 Capra E, Smith J, and Yang G, “ Gene therapy coming of age: Opportunities and challenges to getting ahead ,” October 2, 2019, McKinsey.com. upfront costs are high (often in the range of $500,000 to $2,000,000 per treatment), benefits are realized over time, and treatment is complex, with unique infrastructure and supply chain requirements. In response, both traditional healthcare players (payers, manufacturers) and policy makers (for example, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services) 16 Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, “Medicaid program; establishing minimum standards in Medicaid state drug utilization review (DUR) and supporting value-based purchasing (VBP) for drugs covered in Medicaid, revising Medicaid drug rebate and third party liability (TPL) requirements,” Federal Register , June 19, 2020, Volume 85, Number 119, p. 37286, govinfo.gov. are considering innovative models that include value-based arrangements (outcomes-based pricing, annuity pricing, subscription pricing) to support flexibility around these new modalities.

Innovations also are accelerating in pharmaceutical distribution and delivery. Non-traditional players have entered the direct-to-consumer pharmacy space to improve efficiency and reimagine customer experience, including non-healthcare players such as Amazon (through its acquisition of PillPack in 2018) and, increasingly, traditional healthcare players as well, such as UnitedHealth Group (through its acquisition of DivvyDose in September 2020). COVID-19 has further accelerated innovation in patient experience and new models of drug delivery, with growth in tele-prescribing, 17 McKinsey COVID-19 Consumer Survey conducted June 8, 2020 and July 14, 2020. a continued shift toward delivery of pharmaceutical care at home, and the emergence of digital tools to help manage pharmaceutical care. Select providers have also begun to expand in-home offerings (for example, to include oncology treatments), shifting the care delivery paradigm toward home-first models.

A range of new models to better integrate pharmaceutical and medical care and management are emerging. Payers, particularly those with in-house pharmacy benefit managers, are using access to data on both the medical and pharmacy benefit to develop distinctive insights and better coordinate across pharmacy and medical care. Technology providers, together with a range of both traditional and non-traditional healthcare players, are working to integrate medical and pharmaceutical care in more convenient settings, such as the home, through access to real-time adherence monitoring and interventions. These players have an opportunity to access a broad range of comprehensive data, and advanced analytics can be leveraged to more effectively personalize and target care. Such an approach may necessitate cross-segment partnerships, acquisitions, and/or alliances to effectively integrate the many components required to deliver integrated, personalized, and higher-value care.

Creating and capturing new value

These materials are being provided on an accelerated basis in response to the COVID-19 crisis. These materials reflect general insight based on currently available information, which has not been independently verified and is inherently uncertain. Future results may differ materially from any statements of expectation, forecasts or projections. These materials are not a guarantee of results and cannot be relied upon. These materials do not constitute legal, medical, policy, or other regulated advice and do not contain all the information needed to determine a future course of action. Given the uncertainty surrounding COVID-19, these materials are provided “as is” solely for information purposes without any representation or warranty, and all liability is expressly disclaimed. References to specific products or organizations are solely for illustration and do not constitute any endorsement or recommendation. The recipient remains solely responsible for all decisions, use of these materials, and compliance with applicable laws, rules, regulations, and standards. Consider seeking advice of legal and other relevant certified/licensed experts prior to taking any specific steps.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, our research indicated that profits for healthcare organizations were expected to be harder to earn than they have been in the recent past, which has been made even more difficult by COVID-19. New entrants and incumbents who can reimagine their business models have a chance to find ways to innovate to improve healthcare and therefore earn superior returns. The opportunity for incumbents who can reimagine their business models and new entrants is substantial.

Institutions will be expected to do more than align with growth segments of healthcare. The ability to innovate at scale and with speed is expected to be a differentiator. Senior leaders can consider five important questions:

- How does my business model need to change to create value in the future healthcare world? What are my endowments that will allow me to succeed?

- How does my resource (for example, capital and talent) allocation approach need to change to ensure the future business model is resourced differentially compared with the legacy business?

- How do I need to rewire my organization to design it for speed? 18 De Smet A, Pacthod D, Relyea C, and Sternfels B, “ Ready, set, go: Reinventing the organization for speed in the post-COVID-19 era ,” June 26, 2020, McKinsey.com.

- How should I construct an innovation model that rapidly accesses the broader market for innovation and adapts it to my business model? What ecosystem of partners will I need? How does my acquisition, partnership, and alliances approach need to adapt to deliver this rapid innovation?

- How do I prepare my broader organization to adopt and scale new innovations? Are my operating processes and technology platforms able to move quickly in scaling innovations?

There is no question that the next few years in healthcare are expected to require innovation and fresh perspectives. Yet healthcare stakeholders have never hesitated to rise to the occasion in a quest to deliver innovative, quality care that benefits everyone. Rewiring organizations for speed and efficiency, adapting to an ecosystem model, and scaling innovations to deliver meaningful changes are only some of the ways that helping both healthcare players and patients is possible.

Emily Clark is an associate partner in the Stamford office. Shubham Singhal , a senior partner in McKinsey’s Detroit office, is the global leader of the Healthcare, Public Sector and Social Sector practices. Kyle Weber is a partner in the Chicago office.

The authors would like to thank Ismail Aijazuddin, Naman Bansal, Zachary Greenberg, Rob May, Neha Patel, and Alex Sozdatelev for their contributions to this article.

This article was edited by Elizabeth Newman, an executive editor in the Chicago office.

Explore a career with us

Related articles.

The great acceleration in healthcare: Six trends to heed

When will the COVID-19 pandemic end?

Healthcare innovation: Building on gains made through the crisis

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

Turning Value-Based Health Care into a Real Business Model

- Laura S. Kaiser

- Thomas H. Lee

Examples from four organizations that are doing it.

The shift from volume-based to value-based health care is inevitable. Although that trend is happening slowly in some communities, payers are increasingly basing reimbursements on the quality of care provided, not just the number and type of procedures. But because most providers’ business models still depend on fee-for-service revenues, reducing volume (and increasing value) cuts into short-term profits. How, then, are innovative providers redesigning care so that, despite financial pain in the short term, they achieve long-range success?

- Laura S. Kaiser is the executive vice president and chief operating officer of Intermountain Healthcare.

- Thomas H. Lee , MD, is the chief medical officer of Press Ganey. He is a practicing internist and a professor (part time) of medicine at Harvard Medical School and a professor of health policy and management at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

Partner Center

Business Design Tools

Business Model Canvas

Key partners.

Who are your key partners?

Key Activities

What are the activities you perform every day to deliver your value proposition?

Value Proposition

What is the value you deliver to your customer? What is the customer need that your value proposition addresses?

Customer Relationships

What relationship does each customer segment expect you to establish and maintain?

Customer Segments

Who are your customers?

Key Resourcess

What are the resources you need to deliver your value proposition?

How do your customer segments want to be reached?

Cost Structure

What are the important costs you make to deiliver the value proposition?

Revenue Streams

How do customers reward you for the value you provide them?

5 Effective ways to use the tool

Understanding your current state.

The business model canvas is great for mapping out the current state of your enterprise, business unit or team. It helps you to look at the mechanics of how you create, deliver, and capture value. It can really help to flush out your understanding of strengths and weaknesses. This can lead to insights and a general consensus of where you might need to invest time or money to improve how you operate. At the very least, you can build strong team alignment by understanding your current state, which will also serve you well as the foundational starting point for any future strategy design work.

As an innovation tool

Got a great idea? Let’s get the business model canvas out and get to grips with how the idea will work in the real world. Using multiple canvases, make use of the tool to map out as many options as you think makes sense to push the thinking from the boring to the extreme. This allows you to quickly run with an idea, nipping it in the bud if there are too many weaknesses or deciding to run with it if the business model has promise. Remember that value proposition design starts with DESIRABILITY. Do you have something that your target customer wants or needs? Back end business model innovation is around FEASIBILITY to deliver the desired product/service at scale. With commercial innovation, we need to analyze if the business model is VIABLE. Can you create and deliver value in a way that makes money and is sustainable?

As a storytelling tool

What better way to get across an idea to a potential investor (internal or external) than to show them the robustness of your thinking in a way that grabs their attention and tugs at the emotions? The business model canvas can be used to demonstrate real business rigor and to show that you’ve covered the fundamentals. Let’s paint a clear picture of the path to success.

As a resource planning tool

It’s easy to forget about the “back end” of your business. Map it out to make sure you have thought of everything that is necessary to get your business or innovation opportunity off the ground. It’s good to get really specific here and get into the guts of what resources you need, partners you need to work with and what you need to invest money into. Think about what is really KEY to the business when it comes to resources (people, systems, IP, data, products, culture, funds, etc) and what activities drive the use of the resource. Where does the time get spent?

As a "making it real" tool

Let’s get specific and let’s see some numbers. The tool can show the reality of the business at a deeper level when you show numbers. Adding data into the equation keeps things grounded in reality, and it highlights the key aspects of the business case. This can help you to assess where you should be focusing your resources to improve the overall model and where you are wasting your time and money. Think about actualizing your main revenue streams. What are your average transaction values? What is the reality behind your cost structure? What is your number one channel? What proportion (%) of time is spent across your key activities? There are lots of ways to make use of numbers, percentages, and rankings to bring the business model canvas to life.

Be generous with terminology

Remember that these tools are fundamentally a way of facilitating complex conversations. The terms within the tool should ideally be concrete and specific, but at the very least they should be consistent. Your “customers” aren’t always the people buying your product. They could include the people running the franchise for your product, distributors, or caregiver to the ‘end user’. Sometimes, you can put the same people in both “customers” and “partners”. The “revenue streams” don’t have to just be money. They can be anything that represents captured value for your business, like technical expertise or even improved employee wellbeing. Explore the possibilities that work for you.

Really nail the market facing side

The right hand side of the canvas is what the world sees. This is the most vital part of the canvas as far as obtaining and retaining customers. Make sure you take your time with these sections so you don’t miss any key information or angle. Value proposition design is obviously at the heart of this.

Keep the model in mind for general business discussions

We call this “on-the-fly” mode. Having conversations about a business or a business proposal can often be intimidating or daunting. If you keep the 9 building blocks of the business model canvas in mind you can be sure you discuss the key building blocks of any venture.You really don’t need to wait and always use this tool within workshop settings. Push yourself to see where you can bring its value to use.

Challenge the use of vague terms

There are certain words that get banded about at every business development meeting. Words like “channels” and “marketing” are not specific enough to put on a sticky note and populate your canvas. What exactly do we mean by these? Don’t shy away from getting really detailed with what you put down on the canvas. It’s easy to brush over certain topics with generalizations, but getting specific will give you a much more robust model that leaves little to interpretation. You should encourage your team to really get messy on the first pas; then you have an opportunity to sense make and work on a clean and more specific version.

Create a gallery of options

The great thing about using sticky notes on these canvases is that you can quickly move or replace ideas to switch up the story you’re telling. With this in mind, it’s always a great idea to come up with a load of different options for each so that you can test out different scenarios or business options. At the more macro level, when using the business model canvas as an innovation tool, consider creating a gallery of business model options. This can allow for a strong mixture of extreme thinking and practical versions.

Use it as a team, build common language

Although this canvas is great for building out visualizations as a solo exercise, it’s far more powerful when used as a team. Include people from different departments or with different expertise to provide as many perspectives as possible. The team element will drive powerful ideas, bring together groups in a rapid way, and help with better decision making on what to focus on.

You’ll need an account to access the downloads

Already have an account, create an account, more great tools.

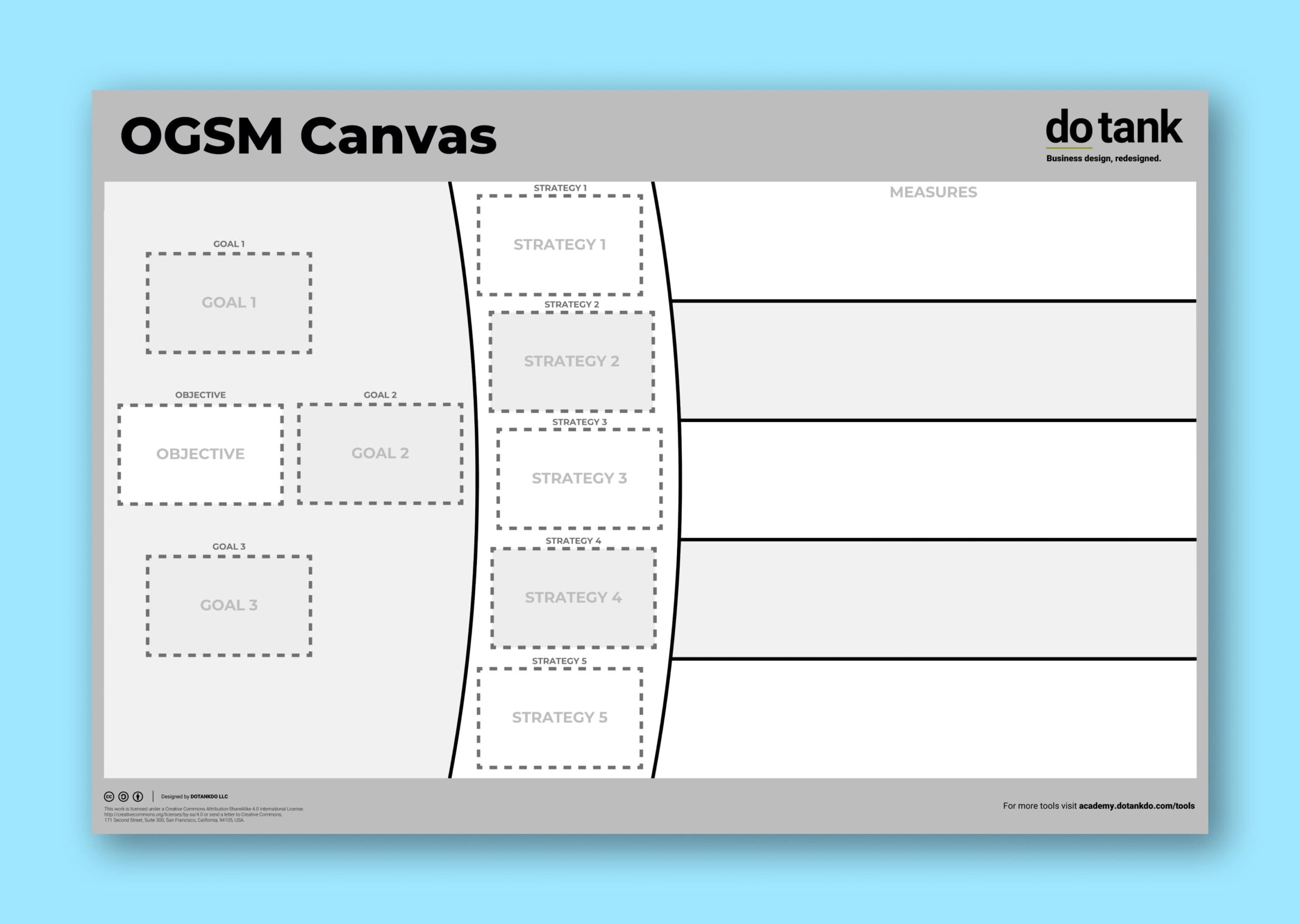

OGSM Canvas

Business Design Tools The OGSM Canvas is a general purpose tool fpr helping to put strategies into action. It focuses on objectives, goals, strategies, and

Swiss Cheese Model

Business Design Tools The Swiss Cheese Model is a metaphor used in risk analysis and risk management. It illustrates how various layers of defence, represented

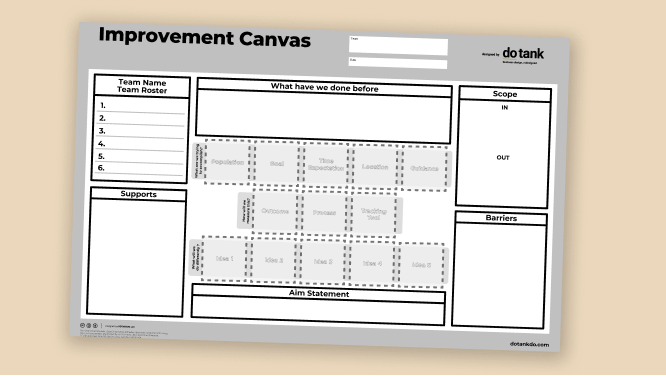

Improvement Canvas

Business Design Tools This canvas utilizes the model for improvement to establish an aim statement and high level project plan. Identify your team, what supports

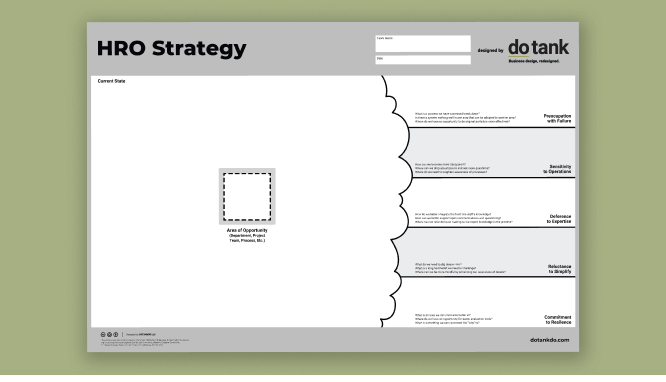

HRO Strategy Canvas

Business Design Tools HRO Strategy Canvas is useful as you explore applying tried and tested principles of high reliability organizations to your healthcare organization to

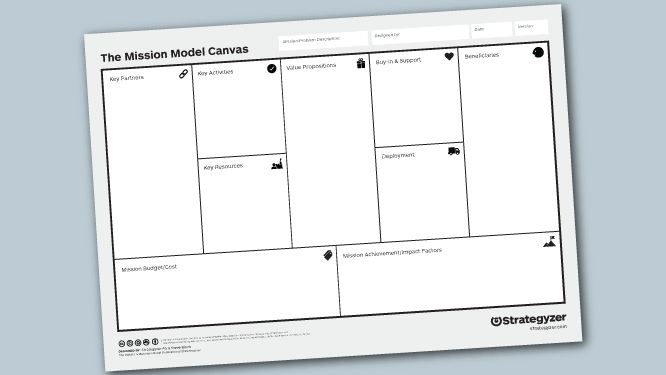

Mission Model Canvas

Business Design Tools The Mission Model Canvas is a strategic planning tool that builds upon the foundation of the traditional Business Model Canvas, but with

Clinician Well-Being Canvas

Business Design Tools The Clinician Well-being Canvas serves as a specialized healthcare tool designed to enhance the overall wellness of clinicians and other healthcare professionals.

Registration

Username or E-mail Password Remember Me Forgot Password

- Open access

- Published: 02 December 2014

Towards a framework for business model innovation in health care delivery in developing countries

- Ramon Castano 1

BMC Medicine volume 12 , Article number: 233 ( 2014 ) Cite this article

11k Accesses

9 Citations

Metrics details

Uncertainty and information asymmetries in health care are the basis for a supply-sided mindset in the health care industry and for a business model for hospitals and doctor’s practices; these two models have to be challenged with business model innovation. The three elements which ensure this are standardizability, separability, and patient-centeredness. As scientific evidence advances and outcomes are more predictable, standardization is more feasible. If a standardized process can also be separated from the hospital and doctor’s practice, it is more likely that innovative business models emerge. Regarding patient centeredness, it has to go beyond the oversimplifying approach to patient satisfaction with amenities and interpersonal skills of staff, to include the design of structure and processes starting from patients’ needs, expectations, and preferences. Six business models are proposed in this article, including those of hospitals and doctor’s practices.

Unravelling standardized and separable processes from the traditional hospital setting will increase hospital expenditure, however, the new business models would reduce expenses. The net effect on efficiency could be argued to be positive. Regarding equity in access to high-quality care, most of the innovations described along these business models have emerged in developing countries; it is therefore reasonable to be optimistic regarding their impact on access by the poor. These models provide a promising route to achieve sustainable universal access to high quality care by the poor.

Business model innovation is a necessary step to guarantee sustainability of health care systems; standardizability, separability, and patient-centeredness are key elements underlying the six business model innovations proposed in this article.

Peer Review reports

Health care systems face a growing pressure to meet people’s needs with limited resources. The pressure grows, among other reasons, as a consequence of demographic and epidemiologic transitions, but mostly as a consequence of new medical technologies that generate small incremental benefits at high incremental costs [ 1 ]. This begs the question, why is it that health care technologies increase costs instead of the opposite, as is the case in other industries? Several authors have proposed that health systems should create more value for money [ 2 ] or that they should have a triple aim of better health, better care, and lower costs [ 3 ]. Thus, why do these undisputable goals prove so elusive and health expenditures continue to grow apparently irrespective of value creation? What are the root causes of this apparently uncontrollable problem of sustainability?

The root causes of the problem of sustainability

In a seminal paper in health economics, Kenneth Arrow proposed that uncertainty in the diagnosis and treatment of disease makes it difficult for doctors and hospitals to achieve predictable outcomes [ 4 ]. In addition, large information asymmetries between doctors and patients make it difficult for the latter to drive quality improvements and innovations that yield more value for less money [ 4 ]. On the other hand, those societies that recognize a right to health care, isolate the individual’s willingness or ability to pay from the actual medical care received. This creates a moral hazard problem whereby the marginal benefit of care is far lower than its marginal cost. As a consequence of uncertainty and information asymmetry, non-market institutions emerge to control the potential agency problems that markets or government regulations cannot control by themselves. Professionalism, not-for-profit status of hospitals, prohibition of advertising and price competition, and lack of an obligation to guarantee good outcomes, are at the heart of medical care values, according to Arrow [ 4 ].

These values might seem obvious to people within the health care industry. However, contrasting this industry with others where uncertainty and information asymmetry are not that large, sheds some light about the fundamental problems of current health care systems. Although uncertainty and information asymmetries always exist, it is clear that in markets such as, e.g., personal computers or mobile phones, consumers have enough information and certainty to make choices based on their preferences and willingness to pay and net of risks. Value for money is the driver of competition, quality improvements and innovation, and producers are pushed every day to create new products that yield more value at lower prices. Just think of the price you paid for a laptop computer 10 years ago and its performance as compared to your current computer.

In health care, value is not so obvious to patients. Although every patient wants to have better quality of life and better functional capacity (broadly addressed through the increasingly used concept of patient-reported outcomes), it is less obvious how the patient would assess the short-term clinical outcomes that yield those benefits. Hence the doctor’s role as an agent for the patient, in order to fill the information gaps. As a consequence, doctors and health care providers have been the traditional designers of solutions to patients, which gives them the privilege to create the structures and processes that, provided good compliance to clinical practice, are expected to result in the best possible outcomes. However, patients themselves are isolated from such design, except for those quality attributes that are observable for them, such as amenities and staff interpersonal skills. This role of doctors and providers as designers of solutions gives them a supply-sided mindset. In other industries that are driven by consumers’ search for value for money, the design of value propositions starts from consumers’ needs, expectations, and preferences, i.e., producers have a consumer-driven mindset. Perhaps this is the most basic difference that, based on Arrow’s powerful insights [ 4 ], explains why the health care industry lags behind other industries in creating more value for each dollar spent.

However, doctors and providers do not deliberately ignore that creating value for patients is a paramount goal for their day to day work. The problem lies in how value is defined. Value in health care should be defined as better outcomes for each dollar spent, and outcomes should be defined around patients, not just around compliance with processes, or around a number of services provided or a simplistic view of patient satisfaction [ 2 ]. This begs the question, why is it not possible for doctors and health care providers to guarantee better outcomes to such an extent that value-based competition works the way it does in other industries? According to Christensen et al. [ 5 ], another fundamental reason, rooted in the same dysfunctionalities described by Arrow, is the business model of hospitals and doctors’ practices. The authors point to the fact that these two business models are adequate to deal with uncertainty, but when uncertainty is reduced and outcomes become more predictable, different business models must be developed to exploit the advantages of standardization and task shifting [ 5 ]. During the early twentieth century, when these two business models (as we know them today) first emerged, most health care was uncertain. The general hospital and the doctor’s practice were adequate to the nature of the task because they allowed for a wide array of resources and capabilities to deal with the multiple contingencies that are typical of uncertain processes. However, to the extent that scientific evidence improves and outcomes become more predictable, uncertainty is reduced for some health care services. Consequently, the better the evidence, the more predictable the outcomes, and the more likely it will be to streamline the structures and processes that are necessary for these types of services. Streamlining means standardization of processes, and once standardized, those processes can in many instances be delegated to other staff. It is worth noting that standardization by itself does not assure the widespread adoption of the standard, a problem reported by McGlynn et al. [ 6 ].

According to Christensen et al. [ 5 ], a major stumbling block in the road to more value for money is that general hospitals and doctor’s practices mix both standardized and non-standardized processes in the same business model. If standardized processes can be separated from non-standardized ones, the former can be organized in more efficient ways and outcomes will improve because of their high predictability. To the extent that these processes are kept together with non-standardized processes, the variability and uncertainty of the latter will affect the predictability of the standardized processes. It appears then, that the structure of health care delivery is at the root of the problems most health care systems face. It is not that doctors and health care providers are incompetent or deliberately poor performers. Rather, it is the business models underlying medical care which need to be changed. This claim has been summarized by Ashish Jha, who says that “… we deliver 21 st century medicine using 19 th century practices ” [ 7 ]. Porter and Teisberg point that “… the structure of health care delivery is the most fundamental issue ” [ 2 ]. Christensen et al. claim that “ The lack of business model innovation in the health-care industry—in many cases because regulators have not permitted it—is the reason health care is unaffordable ” [ 5 ]. Moreover, McGlynn et al.’s claims regarding unacceptably low rates of adoption of standards, can be interpreted as symptoms of the structural flaws of the prevailing business models [ 6 ].

Many commentators have argued that the problem lies in how doctors and health care providers are paid. Fee-for-service reimbursement creates incentives for demand inducement, and no incentives to achieve better outcomes through care coordination across the entire cycle of care of a given medical condition. The lack of incentives for coordination leads to severe fragmentation of care, which makes it impossible for any provider to be accountable for outcomes when these require coordination among several providers. The quick reaction to the bad consequences of fee-for-service has been to shift towards prospective payment modalities that transfer risk to providers, on the expectation that this will create the incentives to avoid demand inducement and to improve coordination of care.

However, when doctors and providers switch from retrospective to prospective payments but do not change their business models, the perverse incentives associated with fee-for-service (demand inducement, lack of coordination) are replaced with the perverse incentives associated with capitation (cost shifting, skimping on care, and cream skimming). In health systems where providers compete for patients or for contracts with payers, and in the absence of business model changes, both retrospective and prospective payments lead to value destruction at both the provider and the payer level. In health systems without competition and lack of business model changes, value destruction also ensues as a consequence of how providers are paid or how they receive their operating budgets. Therefore, payment mechanisms by themselves do not create enough incentives to increase value. A more fundamental change has to take place: a radical change in business model.

Key elements for business model innovation

It could be argued that standardizability is an important element enabling innovations in business models followed by separability from hospital, and, finally, patient-centered innovation.

Standardizability depends on knowledge about how a process can be structured to achieve an outcome with minimal uncertainty. Therefore, the stronger the scientific evidence explaining how A causes B , the more likely the process will be standardized: the best way to make sure that the expected outcome ( B ) is achieved, is making sure the process ( A ) is strictly followed [ 8 ]. Standardization is a necessary condition for task-shifting. A complex task that is surrounded by uncertainty requires judgment based on expertise and experience. Therefore, it has to be performed by a highly skilled worker. In the opposite sense, a simple task with little or no uncertainty requires little judgment and can be written in a protocol, which can be delegated to a less skilled worker. The most extreme case of delegation is an automatic task that is delegated to a computer or a machine. A good example of an entire process that has been standardized, and therefore delegated, is the application of an immunization schedule for a baby. However necessary, standardization is not a sufficient condition for delegation. Not all that is standardizable can be delegated to less skilled workers. For example, placing a stent in a coronary artery or performing a total hip replacement requires a learning process that cannot be leapfrogged by learning a protocol.

Separability is the principle whereby a given process does not depend on a wide array of equipment, supplies, and workforce, and can be set up in a separate facility with dedicated resources that can be efficiently used, i.e., with little or no idle capacity. Interdependencies in hospital-based processes are typical of complex patients, which makes these processes less separable. For example, a given patient with metastatic lung cancer will require many diagnostic and therapeutic processes and surgical and non-surgical procedures, all requiring a wide variety of specialties, equipment, and consumables. Another patient with the same type of cancer might need a different mix of inputs, depending on the particular characteristics of that patient. Therefore, interdependencies make it very difficult to separate care for patients with metastatic lung cancer in a freestanding facility.

A process of care that is highly standardized and highly separable from a hospital or a doctor’s practice is more likely to be arranged in an innovative business model that widely differs from these two traditional business models. Examples of this are cataract surgery or hernia repair, as performed at Aravind Eye Care System [ 9 ] and Shouldice Hospital [ 10 ], respectively. Nevertheless, these two models have been on stage for several decades, which hardly makes them innovative. The interesting question is why they are not more pervasive in health care systems. One business model that is enabled by both standardizability and separability is that of specialized community health workers. In this model, lay people apply highly standardized protocols for following up patients in post-acute phase and patients with chronic conditions in their community setting. Community workers do not make clinical decisions; they are supervised by doctors or nurses, who make clinical decisions and use them as their “extensors” [ 11 ]. Nonetheless, non-standardizable and non-separable processes can also be reshaped with innovative business models as will be shown below. This means that business model innovation is also possible within the current hospital and doctor’s practice models.

The third key element for innovation is patient centeredness, or more broadly, person centeredness. As said above, the supply-side mindset of health care providers makes it difficult for them to understand patients’ needs, expectations, and preferences, and to see them as opportunities for innovation. The farthest that most providers go into this realm is to focus on patient satisfaction with facilities and interpersonal skills of staff. However, patient-centeredness goes far beyond this oversimplifying approach. A case in point is care for rheumatoid arthritis. Two therapeutic goals are key in caring for these patients: prevention of structural damage and control of symptoms; abrogation of inflammation achieves these two goals [ 12 ]. According to the author’s own unpublished research in Bogota, Colombia, from many doctors’ perspective, it is enough to see the patient every one to three months to keep track of levels of disease activity. However, when a patient has a flare, she wants to see the doctor immediately. However, the typical business model of an ambulatory care center is not adequate to deal with non-scheduled visits, and to deal with the processes and activities required for the short-term management of flares. Therefore, patients must attend an emergency room or visit another doctor, with the consequent fragmentation of the cycle of care and coordination problems. Managing short-term symptoms is much more important from the patient perspective than from the doctor’s. However, a business model that is designed from the doctor’s perspective to achieve long-term goals does not meet patient needs, expectations, and preferences in the short term.

This case illustrates the gap between a supply-sided mindset and what consumers need, expect, or prefer. It does not matter how well the staff treats the patient in terms of interpersonal manners or how sympathetic they are to patient complaints. It does not matter how convenient the facility is designed in terms of physical access, waiting rooms, and amenities. The real problem is that the whole business model has to be redesigned to be able to deal with how the patient experiences illness. The traditional supply-sided mindset of doctors and health care providers is, in fact, a tremendous opportunity for business model innovation, as illustrated with the rheumatoid arthritis case. Most other industries have become very sophisticated in anticipating consumer’s needs, expectations, and preferences in order to come up with new value propositions to win the race for consumer votes. This head-to-head race has led to repeated disruptions that have yielded much better products and services at lower prices. Health care lags far behind those industries, so the opportunities for innovation are immense, just by turning back to patients and understanding their needs, expectations, and preferences in a much deeper way than the oversimplifying traditional approach to patient satisfaction.

Six business models instead of one

The process of care can be simplified into three steps: diagnosis, treatment, and self-care/self-management. Each of these steps has both standardized and non-standardized components. A simple way to understand how standardizable and non-standardizable processes allow for innovation in health care delivery models is to depict them as six separate building blocks that can be rearranged in different patterns. Table 1 illustrates this framework. These six blocks are mixed in the current business models of hospitals and doctors’ practices, which is partly the source of their dysfunctionality, as shown above.

The framework in Table 1 allows for six separate categories, each with its own business models, as follows:

Medical conditions for which diagnosis and treatment are highly standardized (blocks 1 and 2). This category includes, for example, diarrhea, minor sunburns, athlete’s foot, etc. These conditions are currently the focus of retail clinics in the United States [ 13 ] and telephone assistance business models. In these two models, the process of care is standardized, can be delegated to non-physicians, and operates outside hospitals and doctors’ practices. The business model of community health workers cited above is another example of this category.

Medical or surgical treatments that are highly standardized such as hernia repairs, cataract surgery, or kidney transplantation (block 2). In this category, some or all activities are highly standardized, and some of the most standardized ones are delegated to non-physicians [ 9 ]. Although cataract surgery and hernia repairs are highly separable from general hospitals, kidney transplantation is not separable, particularly the surgical procedure. The high level of standardization of these processes has deserved them the name “focused factories” [ 14 ]. When the process is not separable from the general hospital, the figure of “a hospital within a hospital” allows for keeping interdependencies while avoiding the interference of non-standardized processes [ 8 ].

Diagnostic processes (block 4). In this category, the idea is to separate the diagnostic process from the treatment decision. This separation aims to avoid the framing bias that makes it more likely that a doctor interprets signs and symptoms through the lens of those medical conditions he or she knows how to treat, or is familiar with. Although it could be argued that a diagnostic algorithm is in fact a standardized process, it is clear that, for a given patient, it cannot be anticipated which of the diagnostic possibilities she has, until the process of hypothesis testing advances through the algorithm. To avoid framing bias, the diagnostic process should be performed in an interdisciplinary way and an explicit process has to be put in place to force clinicians to share their perspectives before making a decision about diagnosis.

Self-care and self-management (blocks 3 and 6). This category includes many processes that are highly standardized, such as taking medications, applying non-pharmacological therapies, changing habits, and adopting healthy lifestyles. Other processes, such as responding to the particular psychological or social needs of a given patient, are not standardizable. Both processes can be dealt with more effectively through peer-support communities [ 15 ]. Christensen et al. propose the business model of facilitated networks: web-based or real groups of people that share common interests [ 5 ]. In this case, the common interest is a medical condition, and the network members support themselves to reinforce positive behaviors and discourage negative ones. The classic example of this category is Alcoholics Anonymous, but modern-time facilitated networks have become pervasive thanks to the internet [ 5 ].

Integrated care of medical conditions (blocks 1, 2, 4, and 5). This category derives from Porter and Teisberg’s proposition of Integrated Practice Units, which are meant to create value around medical conditions, covering the complete cycle of care, including comorbidities [ 2 ]. In this category, standardized and non-standardized processes are mixed, but focused on a given medical condition or set of co-occurring conditions. However, risk stratification of patients typically shows that a big share of patients with a given condition are highly to moderately standardizable and their outcomes relatively predictable, while a minor share are more complex and non-standardizable. Chronic conditions, such as diabetes, heart failure, or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, are more likely to benefit from this business model.

Non-standardized processes of diagnosis and treatment (blocks 4 and 5). These are the typical processes that made the bulk of the workload at hospitals and doctors’ practices, when most health care was highly uncertain because of a lack of evidence. As scientific evidence allows for better predictability of outcomes in some areas of health care, standardization is more likely to be achieved. If standardized processes of care can also be separated from hospitals and doctors’ practices, these latter two business models will end up focusing on non-standardized, non-separable processes. It is obvious that these two pillars of health care delivery will not disappear, but it could be argued that their business models will be reshaped and their strategic focus will shift from “everything-to-everybody” to a narrower focus on those processes of care that exhibit a larger degree of uncertainty and a lower degree of separability.

In summary, uncertainty and information asymmetries give rise to a deeply-rooted supply-side mindset in health care delivery. The prevailing business models of hospitals and doctor’s practices emerged from this mindset and have not radically changed ever since. Standardizability and separability, along with patient-centeredness, allow for six new types of business models in addition to the traditional business models of hospitals and doctor’s practices. These radical changes in business models, more than just changing payment mechanisms, are more likely to yield real changes in how health care providers deliver more value for each dollar spent.

General hospitals usually cross-subsidize loss-making service lines with profit-making ones, so their sustainability depends critically on this compensatory scheme in order to distribute the heavy overhead burden [ 5 ]. This is one argument for hospitals to oppose the separation of service lines in freestanding facilities, particularly those that are more profitable.

However, it could be argued that, depending on how pricing is reshaped to reflect actual costs of production, this complex combination of cross subsidies can be reversed. Business models focused on highly standardized processes will be more able to bundle-price their services on a fee-for-outcome basis, and prices will be more likely to reflect marginal costs. General hospitals will be more able to price complex processes on a fee-for-service basis but also reflecting marginal costs. Therefore, competition will be more likely to result in higher value for money, just the way it happens in other markets.

Doctor’s practices, on the other hand, can also be reshaped into two different business models: one for highly standardized processes, such as minor ailments, routine follow-up of patients with chronic non-complex conditions, immunizations, and screening tests; and one for those patients that require further study or are more complex and non-standardized [ 5 ]. Standardized processes can be delegated to other health care workers without decreasing quality, and the most expensive and scarce workforce can be focused on those processes in which it is strictly necessary [ 16 ].

It can be expected that overall health system efficiency will benefit; hospitals and doctor’s practices will probably become more expensive, even though their prices reflect marginal costs. However, the other five business models will cause prices to decrease as a consequence of a more market-like competition. The net effect of both changes would be expected to be positive, i.e., net efficiency gains for the health system, or put another way, more value for money as a consequence of value-based competition. How does it impact equity and poverty? According to Scott et al. [ 17 ], universal coverage to improve access to care by the poor is not enough. They cite the experience of a conditional cash transfer program in India that improved access to maternity care and institutional delivery of babies, but did not improve maternal mortality rates. Therefore, the goal of universal coverage has to be rephrased to say “universal access to high-quality care for the poor.” Otherwise health policies aimed at universal coverage will be futile, health care will be less affordable and more inequitable, and health care spending will be more inefficient.

The quick answer to how business model innovations can improve equity in access to high-quality care is that a large part of the innovative business models that follow the lines of this article have emerged mostly in India and sub-Saharan Africa but also in other developing countries [ 18 ]. Surgery for cataracts and other eye conditions at Aravind Eye Care System and LV Prasad Eye Institute, birth attendance and maternity care at Life Spring, heart surgery and hip replacement at Narayana Hospitals, and cancer treatment at Health Care Global, are examples of low-cost high-quality services that are accessible to the poorest in India. Sala Uno is an application of the Aravind business model in Mexico. Penda Health and One Family Health are examples of primary care services in Africa. Medicall, Grand-Aides, and Aprofe are examples in Latin America and the United States [ 19 ]. It is clear that business model innovations in health care delivery hold a promise for affordable, high value-for-money solutions for the poorest.

Innovations in health care delivery models are a necessary step to evolve towards a more market-like environment where competition among providers leads to more value for money. The traditional business models of general hospitals and doctor’s practices are not adequate for every kind of task, and this explains part of the sustainability problems of health care systems. New business models are emerging that shed light on this claim, but they show diverse degrees of innovation along the lines of standardizability and separability, as well as patient centeredness.

Author’s contribution

This manuscript is entirely written by the author, and reflects his original thoughts based on his personal experience and knowledge and other authors’ concepts and opinions, as properly quoted.

Author’s information

The author is a private independent consultant with background in health policy and management. Recent work focuses on innovation in healthcare delivery models, not only as a consultant to clients interested in implementing these innovations, but also as an entrepreneur.

Smith S, Newhouse J, Freeland MS: Income, insurance, and technology: why does health spending outpace economic growth?. Health Aff. 2009, 28: 1276-1284. 10.1377/hlthaff.28.5.1276.

Article Google Scholar

Porter M, Teisberg E: Redefining Health Care. 2006, Harvard Business School Publishing, Boston

Google Scholar

Berwick D, Nolan T, Whittington J: The triple aim: care, health and cost. Health Aff (Millwood). 2008, 27: 759-769. 10.1377/hlthaff.27.3.759.

Arrow K: Uncertainty and the welfare economics of medical care. Am Econ Rev. 1963, 53: 941-973.

Christensen C, Grossman J, Hwang J: The Innovator’s Prescription. 2009, McGraw Hill, US

McGlynn EA, Asch SM, Adams J, Keesey J, Hicks J, DeCristofaro A, Kerr EA: The quality of health care delivered to adults in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2003, 348: 2635-2645. 10.1056/NEJMsa022615.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Jha A: 21st Century Medicine, 19th Century Practices. 2011, Harvard Business Review, Boston

Bohmer R: Designing Care. 2009, Harvard Business School Publishing, Boston

Govindarajan V, Ramamurti R: Delivering World-Class Health Care, Affordably. 2013, Harvard Business Review, Boston

Heskett JL: Shouldice Hospital Limited. , [ http://www.hbs.edu/faculty/Pages/item.aspx?num=21244 ]

Thomas C: A structured home visit program by non-licensed healthcare personnel can make a difference in the management and readmission of heart failure patients. J Hospital Administration 2014, 3: Thomas..

Smolen JS, Aletaha D, Bijlsma JWJ, Breedveld FC, Boumpas D, Burmester G, Combe B, Cutolo M, de Wit M, Dougados M, Emery P, Gibofsky A, Gomez-Reino JJ, Haraoui B, Kalden J, Keystone EC, Kvien TK, McInnes I, Martin-Mola E, Montecucco C, Schoels M, van der Heijde D: Treating rheumatoid arthritis to target: recommendations of an international task force. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010, 69: 631-637. 10.1136/ard.2009.123919.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Bohmer R: The rise of in-store clinics: threat or opportunity?. N Engl J Med. 2007, 356: 765-768. 10.1056/NEJMp068289.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Herzlinger R: Who Killed Health Care?. 2007, McGraw Hill, US

Peer Support Programmes in Diabetes: Report of a WHO Consultation, 5-7 November, 2007. 2008, WHO, Geneva

Optimizing Health Workers Roles to Improve Access to Key Maternal and Newborn Health Interventions through Task Shifting. 2012, WHO, Geneva

Scott KW, Jha AK: Putting quality on the global health agenda. N Engl J Med. 2014, 371: 3-5. 10.1056/NEJMp1402157.

Henke N, Ehrbeck T, Kibasi T: Unlocking Productivity through Healthcare Delivery Innovations. Lessons from Entrepreneurs around the World. , [ http://www.ipihd.org/images/PDF/UnlockingProductivity%20booklet.pdf ]

International Partnership for Innovative Healthcare Delivery: IPHD Innovators . , [ www.ipihd.org/innovations/ipihd-innovators ]

Download references

Acknowledgments

This work has been performed without funding. The author acknowledges the comments received from two referees.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Organización para la Excelencia de la Salud, Bogota, Colombia

Ramon Castano

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Ramon Castano .

Additional information

Competing interests.

As a consultant for private healthcare providers and payers, the author has financial interest in promoting innovative healthcare delivery models in Colombia and Latin America, particularly with Grand-Aides International, but others will come in the future. The views expressed in this article are the author’s own, and do not necessarily represent the views of Organización para la Excelencia de la Salud.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly credited. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Castano, R. Towards a framework for business model innovation in health care delivery in developing countries. BMC Med 12 , 233 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-014-0233-z

Download citation

Received : 04 August 2014

Accepted : 10 November 2014

Published : 02 December 2014

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-014-0233-z

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Business model innovation

- Quality care

- Standardization

- Separability

- Patient-centeredness

BMC Medicine

ISSN: 1741-7015

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- View My Profile

- View My Company

Business Model Innovation in Healthcare

When we think of innovation in health care, we often think of technologies such as imaging equipment, new pharmaceutical, vaccines, or new digital technologies including machine learning. However, business model innovation can be a critical part of such innovations, and can even be done with existing technologies in many cases.

For example, Dr. Jeffrey Brenner, a primary care physician practicing in Camden, New Jersey knew he had to do something when he uncovered a large nursing home and a residential tower housing mainly low-income families in the city accounted for over 4000 hospital visits and 200 million dollars in healthcare bills over the course of five years. His plan was to organize these patients to receive care in the community, rather than in the emergency services.

The “basic stuff” that the patients deserved were provided accordingly. They include home visits with nurse practitioners, regular blood sugar and blood pressure checks and education on drug adherence, healthy lifestyle and so on. Dr. Brenner’s strategy worked. He had successfully reallocated some of the precious, yet scarce healthcare resources to a small subset of super-utilisers or patients with high-needs.

Stephen Chick, Professor of Technology and Operations Management and Academic Director of Health Management Initiative at INSEAD used Dr. Brenner’s story to elucidate the role of innovation in present day healthcare. Modern day healthcare is challenged by many factors. Unfortunately, spending more money does not always lead to better outcomes.

“It’s not a gap but a chasm between what healthcare needs to do and what people demanded,” Professor Chick said. “The real solution is to innovate, not just by adding scientific or technological advances into existing processes but finding new ways of doing things”.

What Dr. Brenner did is an example of a Business Model Innovation (BMI) which involves segmenting and dealing with costly outliers using a different process. He is not alone.

Dr. Eugene Shum and the Eastern Health Alliance in Singapore also supported elderly with care and social needs to help avert costs and painful readmissions. In one of the initiatives, there were trained volunteers in 18 neighbourhoods to keep an eye on senior residents living near them. There would also be motion sensors in different zones to estimate the activity level of an elderly at home and picking up anomalous events like falling or fainting.

Both Dr. Brenner and Dr. Shum’s examples are very similar to the use of the advanced analytics to identify “high cost” or “high value” customers in other sectors such as equipment maintenance services or financial services.

Professor Chick believes BMI is helpful to bring insights and finding new ways to deliver care or creating health. After all, technology innovation is hard to map from one industry to another, but patterns of finding novel ways of matching supply and demand can be mapped across sectors more easily.

To do so, Professor Chick suggests a BMI audit, which entails assessing key strategic decisions and areas requiring big asset commitments such as time, people and money. At the same time, look out for the three “I”s or sources of potential losses due to information asymmetry; incentive misalignment, and ways of interfacing customers. From there, coming up with ways to mitigate these potential losses through redesigning process, services or ways to do things.

Based on the audit, one can then start to explore how to find innovative business models and there are two ways of doing so. Assessing whether continuous improvement is enough or whether a very different business model might do better. If the latter is deemed suitable, then initiating a search process is helpful. Do take note that search is different from analysis, search identifies innovation opportunities while analysis is a core part of continuous improvement.

Professor Chick added, apart from targeting outliers, there is also a BMI template suggesting supply chain reintermediation. For example, online food ordering platforms like FoodPanda are intermediaries serving both restaurants and diners. On one hand, restaurants are spared from the needs to invest on full time delivery staff. On the other, customers have the convenience of choosing from multiple dining choices. This can be mapped to the health sector.

Meddo is an India-based company which places phlebotomists in outpatient clinics. The phlebotomists, who also are trained to be clinic managers, take lab samples from patients or doctors to the labs and deliver medications from doctors to the patients. In that sense, Meddo aggregates the demands for lab services while simplify inventory management for medications, reducing cost and improving patient journey.

Other BMI archetypes as told by Professor Chick included postponing production decisions until demand is better known and doing so through operational flexibility and listening to customers and risk-sharing. For an example of innovating with risk sharing, service agreements that are paid for as a function of MRI uptime rather than paid for when MRI machine is broken and needs fixing. This can be implemented in terms of outcomes based reimbursement, like Medicare.

Regardless of which, Professor Chick said “we are making a lot of assumptions about average patient, cost and benefit of healthcare in the traditional business model. Thus, we need to look at the challenges, re-think the order of events, and set up a special practice to deal with those outside the norm, to save money and deliver much better care to more people”.

Bear in mind that at the end of the day, it’s not “throwing technology” or “AI” or “digital medical records” at the problem. It is stepping back and gaining inspiration across sectors to strategically think about ways to improve the health of populations differently. It is moving beyond adopting innovative technologies and strategically rethinking how health can be better created.

RELATED CONTENT

Exclusive Interview: Managing Director, Dr. Sardjito Central...

Dr. dr. Darwito on his vision for digital transformation.

Exclusive: How the UK uses health tech to fight isolation an...

Interview with Noel Gordon, Chairman of NHS Digital, the tech solutions provider of NHS.

Exclusive Interview: CEO, Dr. Kariadi General Hospital Medic...

Hospital Insights Asia speaks to Chief Executive Dr Agus Suryanto on his vision for 2019.

Like this story? Subscribe for more

Subscribe to our newsletter by providing your name and email address in the form below

- Activity Diagram (UML)

- Amazon Web Services

- Android Mockups

- Block Diagram

- Business Process Management

- Chemical Chart

- Cisco Network Diagram

- Class Diagram (UML)

- Collaboration Diagram (UML)

- Compare & Contrast Diagram

- Component Diagram (UML)

- Concept Diagram

- Cycle Diagram

- Data Flow Diagram

- Data Flow Diagrams (YC)

- Database Diagram

- Deployment Diagram (UML)

- Entity Relationship Diagram

- Family Tree

- Fishbone / Ishikawa Diagram

- Gantt Chart

- Infographics

- iOS Mockups

- Network Diagram

- Object Diagram (UML)

- Object Process Model

- Organizational Chart

- Sequence Diagram (UML)

- Spider Diagram

- State Chart Diagram (UML)

- Story Board

- SWOT Diagram

- TQM - Total Quality Management

- Use Case Diagram (UML)

- Value Stream Mapping

- Venn Diagram

- Web Mockups

- Work Breakdown Structure